Deductions from the DNA database

The Home Office maintains that retaining the DNA profiles of innocent people on the DNA database increases the chances of solving future crimes. But what’s the evidence for this?

A close reading of the recently-published Annual Report for 2007-08 and 2008-09 of the National DNA Database might be expected to provide it - but it doesn’t.

The report includes the number of matches between DNA subject-profiles and crime-scene profiles, but does not tell us whether those links were to people who had been convicted of crimes, or to people whose DNA had been taken only for them not to be charged with, or to have been found not guilty of, the crime that instigated the taking of the sample.

Given that this is currently a matter of controversy, with the Home Office proposing to retain “innocent” samples for six years, the omission of any evidence that the policy will increase the clear-up rate is astonishing, and regrettable.

The omission is readily remediable, however, and with relatively little effort. What needs to be done is for the successful matches to be scanned to identify the guilty/innocent status of the individual from which they came. For murder, manslaughter, attempted murder and other suspicious deaths, the report tells us on page 34, there were 523 successful matches, so it would be possible to scan all of these.

For commoner crimes, the numbers are greater, and so a sampling procedure should be followed – a one in 10 representative sample of the successful subject-profile matches for violent and sex crimes and drugs offences (where 5,573 matches were found) and a one in 100 sample of the successful subject-profile matches for burglary, criminal damage, and theft from a vehicle (58,385 matches found).

There is another way of addressing the problem, which is to look at the frequency with which new DNA subject-profiles help to solve unsolved crimes. In 2007-08, a total of 591,028 new subject-profiles were added to the database which, at the time, contained crime-scene profiles from around 312,000 “unsolved” crimes. The report says (page 33) that the match between these new subject-profiles and the “unsolved” crime-scene profiles was 1.5 per cent, from which I conclude that around 8,900 (to the nearest 100) subject-to-‘unsolved crime-scene’matches arose.

The key question is: how many of these 8,900 were subsequently not convicted of the crime for which their DNA profile was initially obtained; what is the overlap (if any) between the type of crime for which they were arrested and the type of crime their profile matched; and what are the demographics – sex, ethnicity and current age – of the 8,900? The report is silent on these points.

In 2008-09, the number increased to 13,300 subject-to-‘unsolved-crime-scene’ matches out of 580,174 newly added subject-profiles (page 11), a rate of 2.3 per cent. This huge increase appears to have come about as a result of a change to an IT system which increased the rate of historical matches. Given the size of the change, more details on what actually happened would have been welcome. We are left to wonder how many past crimes were left unsolved because matches were previously missed at a time that might have influenced the police investigation.

These DNA profile matches are of two sorts: subject-to-scene and scene-to-scene. Fairly often, a DNA sample taken at the scene of crime will match that from an earlier scene, clearly implying the same perpetrator. Between 2007-08 and 2008-09, these scene-to-scene matches increased from 2,861 to 4,139 – a remarkable rise. What it means in practice is that of 49,572 newly-added crime-scene profiles in 2008-09, 8.3 per cent matched existing but “unsolved” crime scenes.

In some cases, the new scene-profile matched more than one existing crime scene. There were 754 that matched two previous scenes, 513 that matched three, 124 that matched four, and 117 that matched five or more previous scenes. Detailed re-investigation of the crime-scenes and the associated police procedures is, or ought to be, under way to suss the modus operandi of, and to arrest, these 117 extreme Houdinis-from-justice. (The explanation for these matches could be simpler: some solved crime scene samples, normally removed when a conviction is obtained, may have been overlooked for deletion.)

The precise procedures by which crime scene profiles are deleted varies from place to place. Deletions occur at the request of the police when a conviction occurs or a case is closed. But new acquisitions exceed deletions, so the “unsolved” crime-scene profiles, which stood at 350,003 at the end of March 2009, are growing at the rate of about 25,000 a year.

Deletion or retention of crime-scene profiles is relatively uncontroversial, though it is perhaps surprising that a national database permits local variations in how police forces interpret the rules. But retention of DNA subject-profiles is a much more contentious issue, where those profiles have come from people subsequently not charged or charged but found not guilty.

Policy differs in Scotland, where “innocent” DNA subject-profiles are retained only in the case of sexual or violent crime for three years – a period repeatedly extendable for an additional two years on application to a sheriff. And so, in the two years covered by the reports, while only 162 subject-profiles were deleted in England and Wales in 2007-08, and 283 in 2008-09, the corresponding numbers in Scotland were 19,211 and 16,562 respectively.

If we scale this up by population, we can estimate that had the deletion policy in England and Wales been the same as in Scotland, the upper limit for the number of deletions would be 211,300 in 2007-08 and 182,200 in 2008-09. (These are estimates because I have not been able to take into account the possibility that the same “innocent” person had been arrested twice in the same year in Scotland, in which case the removal of their profile would count as two removals.)

During 2008-09, the number of profiles on the national database increased by 476,284. That increase might have been 40 per cent lower (as an upper limit) or 20 per cent lower (if two arrests per annum were the worst case) had Scottish provisions applied throughout the UK.

This estimate is consistent with a BBC report, based on parliamentary answers, that 20 per cent of subject-profiles on the database are for people neither charged nor convicted. Since retention is a recent phenomenon, introduced this century, it is reasonable to suggest that the proportion in newly-acquired “innocent” subject-profiles is thereby higher than 20 per cent.

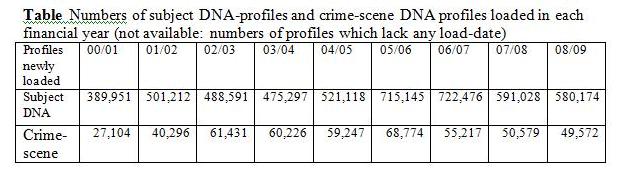

But this, in turn, leads us to another strange discrepancy shown up in the report. In 2007-08 and 2008-09, the acquisition of subject-profiles fell sharply, by more than 100,000 a year (see Table). This is a huge change in policing, or in the committing of crime, about which the report is too cryptic. Was this, perhaps, a temporary staying of the police’s hand in acquisition of innocent DNA subject-profiles while the matter of their prolonged retention was sub judice at the European Court of Human Rights?

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 30/11/2009 - 11:26

The two key words here are relative and family.

It is relatively easy to apprehend criminals - not today or this year - but in the future. Sooner or later a relative of someone who already has DNA on fiel wil be arrested for a crime.

This wil happen because DNA crosses generations. Key indidcators arepereptual.

It is a matter of record that one man ws arrested a few years ago for a crime because his uncle's DNA was already known to police.

So in the strictest sense of the wording, the Home Office is right to maintain/claim that ". . . .the DNA profiles of innocent people on the DNA database increases the chances of solving future crimes." But is that ethical ?

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 01/02/2010 - 23:46

Having re-read this article after absorbing later DNA articles on this website, I feel I have to comment on the following sentence found above:-

"These DNA profile matches are of two sorts: subject-to-scene and scene-to-scene. Fairly often, a DNA sample taken at the scene of crime will match that from an earlier scene, clearly implying the same perpetrator."

The phrase "clearly implying the same perpetrator" troubles me because it is an assumption that is dangerous to make. The point has been made else where and by others regarding the dangers of "transference".

Put in non-DNA terms, if a youth drinks from a can and disposes of the can in a litter bin or in the gutter and that can is then collected by street cleaners but is accidently spilled or dropped off en route that can puts the youth's fingerprints at a possible crime scene. The youth may have be be at one crime scene (or not) but not the other.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 04/02/2010 - 12:32

Thanks for this article, I found it very useful. Just looking at the last part I find it interesting not only how new subject dna went down but for the 2 years prior to this ( 05/06 and 06/07) dip it increased quite so much. Was there a deliberate policy to collect people's dna? Was this curbed not just becasue of the S and Marper case but becasue of the growing public awareness in 2006?

Wilfreda (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 09/02/2011 - 09:17

I have this blog post bookmarked to check out for the new that you have posted to be my reference for my personal statement.