How the panic over rape was orchestrated

For years the Home Office and the former Lord Chancellor’s Department have misled the media about rape statistics – and allowed the media to misinform the public.

Anxiety has grown as a result of the apparent increase in rape offences and the inability to successfully prosecute offenders. Women have been needlessly alarmed for their safety, when the actual threat is much smaller than has been pretended.

Congratulations, therefore, to the Radio 4 programme More or Less and its reporter Ruth Alexander, who have put into the public domain what some advisers engaged by Whitehall committees have known for some time.

This official misinformation, one suspects, was a deliberate policy choice (beginning somewhere around 1988) to ensure that no matter what the cost, rape and sex crimes would climb remorselessly up the political agenda.

Since 1999 the Home Office has known that its methods for calculating rape convictions are wrong. The real conviction rate is not the publicly broadcast 10 per cent but closer to 50 per cent (it varies slightly from year to year). In a Minority Report (1) which I wrote for a Home Office committee in 2000 but which advisers refused to forward to ministers who were then actively considering new rape legislation, the HO were told that they were confusing ‘attrition’ rates with ‘conviction’ rates.

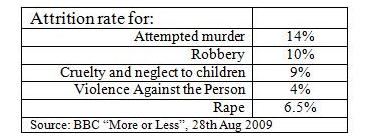

The attrition rate refers to the number of convictions secured compared with the number of that particular crime reported to the police (it must be noted that a crime that is ‘reported’ does not automatically imply that the crime actually took place). The conviction rate refers to the number of convictions secured against the number of persons brought to trial for that given offence.

Rape is the only crime judged by the attrition rate. All others – murder, assault, robbery, and so on – are assessed by their conviction rates. Why? The question is best addressed to Betty Moxon who, in 2000, was head of the Sex Offenders Review Team (SORT) for whom I wrote the minority report.

In the most recent edition of More or Less, broadcast last Friday and still available as a podcast, Ruth Alexander questioned why rape has been made an exception. Referring to a new report soon to be published by London Metropolitan University she said it claimed that Britain had the worst record in Europe for rape convictions. Over recent years, she said, the report showed that the conviction rate had fallen from 10 per cent to 6.5 per cent.

But this is based on the misleading attrition rate. When real conviction rates are calculated on a common basis with other crimes, her report endorses our findings of 2000 (and subsequent years), namely that it is more commonly in the 48-52 per cent bracket. Her latest figure, for 2007, was 47 per cent.

But how are we to judge if that is good or bad ? Comparable figures show that the conviction rate, for instance, for Violence Against the Person was 71 per cent.

In the past the Home Office used to publish annual “Criminal Statistics for England and Wales” which were very accessible. Its present embodiment, published by the Ministry of Justice does not helpfully list murder rates or conviction rates. Nonetheless, Ruth Alexander quoted comparable ‘attrition rates’for other crimes, listed below:

Each year, several million crimes are reported to the police. Most of those listed above can be measured in the tens if not the hundreds of thousands. Sex offences, by contrast, are only 2 per cent to 3 per cent of all reported crime, according to Home Office statistics.

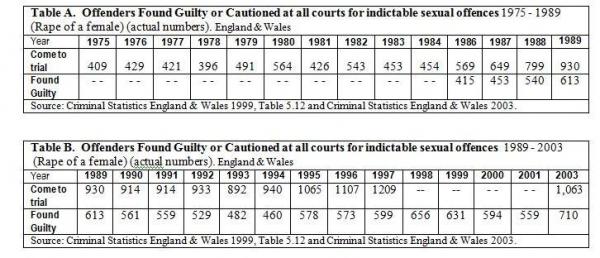

The tables below offer an insight into the official version of events and the truthful version. The range of years encompassed has necessitated 2 tables, A and B. Some figures have been omitted, e.g. from 1975 to 1984 because they cannot be corroborated or are found to deviate where there are two sources, e.g. the UN versus the Home Office.

Both Table A and Table B. show how many allegations of rape actually come to trial and how many offenders are subsequently found guilty. This is the true conviction rate.

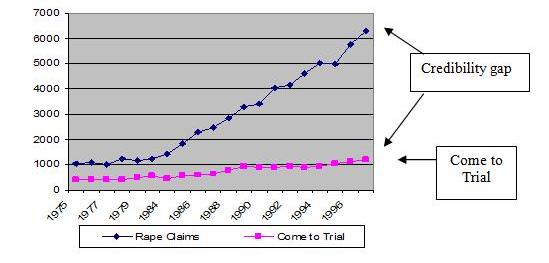

Transformed into a graph the conviction rate (for 1985 to 1997) begins with a very high figure of more than 400 convictions in less than 600 cases. Although the gap has widened by 1997, the two lines nevertheless shadow one another.

This is not the version distributed by the Home Office, to the media and thence to the public Instead, a more unbalanced picture is portrayed – one where unsubstantiated claims of rape are reported as fact and then compared with factual cases that have enough evidence to enable them to come to trial. This gives rise to what can be termed the "Credibility Gap" (see graph below). The upper trend line shows the ever increasing number of reported rapes.

Since 1997 the ‘credibility gap’ has continued to increase year by year to the present day. There are many reasons for the continued rise in the number of claims of rape but few can be related to the way trials are conducted.

Since the 1980s certain of the standard defence options normally available to a person deemed innocent until proven guilty are no longer available in rape cases. The requirement of corroborating evidence, so essential in ordinary criminal cases has been waived for rape cases and is no longer available to the defendant.

Ruth Alexander made the point that reported rapes have not doubled in the last 20 years, as one might suppose as being a reasonable trend, but have increased some 700 per cent. This rate of increase is perhaps the world’s fastest. No other advanced industrialised country appears able to match this rate of increase so it is no wonder, if we accept that all rape claims made to the police are genuine, that our conviction rate is so low. The graph below shows the rise in rape allegations made to the Metropolitan Police.

This must leave a question mark over whether the figures for reported rapes can be relied upon. From New Zealand to Canada to Holland the trend lines for rape are more or less horizontal (ie steady) and vary little from one year to another.

By contrast, the Met Police figures for reported rape show a curve which is surely unsustainable. The experience of New Zealand, which at one point ceased paying compensation to rape victims, is instructive. After a corresponding fall in claims the re-introduction of compensation for rape was followed by a recovery in the number of reported rapes.

As if to acknowledge the discrepancy the Home Office Research Dept has published more than two papers on how this gap between rape claims and rape convictions arises. In essence, their paper, HORS 196, (2) lists over 50 per cent of reported rapes as being without credible evidence to take them to trial.

This is where the ‘attrition rate’ saga begins. Of the initial 483 cases reviewed 25 per cent were ‘no-crime’ and 31 per cent were listed as ‘no further action’ (NFA). Both categories signify a suspicion that the claimed crime did not occur, or did not occur in the way first explained, and requires that the claimant make a retraction before the police can categorise them as ‘no-crime’ or NFA.

(Robert Whiston has served on several Whitehall committees attached to the Home Office, the Lord Chancellor's Department and the Ministry of Justice since 1999. He has written several briefing papers on the level of sexual offending and rape sentencing tariffs both in the UK and abroad.)

[1] “When Justice Collide with Science” by Robert Whiston, June 2000.

[2] See HORS 196, & HORS 293, page 28. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/hors293.pdf

David McCandless (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 03/09/2009 - 17:44

Thank you for an interesting and clarifying article.

May I correct you on a point?

You say in the final paragraph rape cases listed as "no crime" or "no further action" signify "a suspicion that the claimed crime did not occur, or did not occur in the way first explained"

Not always.

Official police guidelines say the "no crime" category covers cases recorded in error, when the offence took place in another jurisdiction, where there was credible evidence that no offence took place and false allegations.

For rape, the percentage of false allegations is around 30% of the "No Crime" figure.

So, of the 483 cases you cite, that would make just 36 false allegations.

source: Home Office HORS293"A Gap Or a Chasm? Attrition in reported rape cases" Feb 2005 p38

http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/hors293.pdf

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Fri, 04/09/2009 - 02:56

Something you should read ...

http://www.harrietharmansucks.com

Amongst other things, it shows how 700 rapes are turned into 70,000 by people like Harriet Harman in order to pursue their own ambitions.

Best

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 05/09/2009 - 17:59

Dear David,

I am sorry if you feel I may have misled you in any way, but the topic is so vast and technical that to cover all aspects comprehensively would have required a lot more column inches and might have been very boring to many readers.

Are you trying to say that of the sample selected by the Home Office, i.e. the 483 cases, 30% were false allegations and the remaining 70% were simply lacking credible evidence ? (I haven't included "cases recorded in error" in the 70% you cite as it is difficult to imagine the police making such a mistake on such a large scale).

With regards your last comment; "So, of the 483 cases you cite, that would make just 36 false allegations", I think if you had worked with or surveyed police surgeons you would find it difficult to make so simple a statement. If you turn to pages 14, 15 and 16 of HORS 196 you have it on a plate. Complaints withdrawn vary from 14% to 42% to 33% (p14). You will also see mention of an earlier HO study by Lloyd & Walmsley (HORS 105, 1989). You will note that the HO definition (HO circular 69/1986) of ‘no crime’ is where; “the complainants retracts completely and admits fabrication” (p14).

Is that not also a definition for false allegation ?

You might find data from the USAF and from FBI records illuminating as to why so many claims are found to be false or are retracted.

IMO we can look forward to the continued politiciastion of both rape and of statistics, eg HORS293, with further HO circulars forcing police to categorise assaults and sexual offences as rapes when they do not merit it.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 09/09/2009 - 00:11

Dear Robert

How does the Home Office know which allegations are false, if they have not gone to trial?

James

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 19/09/2009 - 17:41

Dear James,

i think you had best aak that question after tranforming rape into a less mind numbing crime such as car theft or purse snatching.

Now ask the question - How does the Home Office know which allegations of purse snatching are false ?

The answer should be self-evident - or at least clearer.

Roberrt

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 21/10/2009 - 16:15

Robert,

I understand the argument you have made regarding the comparison between attrition rates and actual conviction rates once a case has gone to trial, however, given that the government estimates that 95% of all rape cases go unreported i do take exception to the overriding suggestion in your article that these high attrition rates are due to false allegations.

It has been notoriously difficult throughout history to secure rape convictions for a multitude of reasons, i imagine your examples of rape cases that have led to convictions are disproportionately 'aggravated rape' cases, when it can be seen that the vast majority of rapes that occur are the 'simple rape'- this is where victims are being let down.

Of course, this argument could go on forever, however i would ask you to consider whether it is the (probably quite influential) views of yourself and your peers which have led to the attitude of the police to rape... "Dave Gee, a former detective chief superintendent... said Britain's low conviction rates were partly due to poor evidence gathering and "indifferent attitudes" towards rape by police.

"Too often, because of the negative mind at the outset, the case is undermined rather than built up," he told The Times newspaper."

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Fri, 23/10/2009 - 11:33

I agree with most of what you have said in your article, which is why this comment is fairly irrelevant politics-wise. But as far as worrying women more than need be goes, I do not believe that that is a bad thing. In fact I would say that girls and young women are becoming less rape-aware once more as more and more figures are published showing the small proportion of outdoor and stranger rapes that occur.

If figures are being massaged to make women more safety conscious then from the public's perspective I do not necessarily see that as a bad thing.

However I have known and worked with many victims of sexual assault and rape and being exposed to the attrition rates rather than the conviction rates has prevented many of them from going to the police.

I would consider that far more damaging and worrying than the political aspect of this situation.

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Fri, 23/10/2009 - 22:08

Dear Anonymous.

Thank you for taking the time to comment. Straight Statistics always tries to deal with actual numbers and not estimates - particularly unsourced estimates.

If you can track down why the government estimates that 95% of all rape cases go unreported you will have made your point (I suspect it is drawn from extrapolating from BCS samples/figures).

In my experience of Gov't press releases they usually defer (when pressed) to estimates from lobby groups and advocacy research - and you know what Frank Furedi said about advocacy research ("A danger to the nation's children", 19 Jan 2004).

(See also Irwin Hyman who, at a meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics (1996), proposed a campaign of what he called 'advocacy research', using bits of research as propaganda to change public policy).

The number of alleged unreported rapes varies enormously from 100,000 pa to 500,000 pa depending on the lobby group concerned. How can you realistically count what is not agreed and is someone's guess and is not evidentially there to quantify ?

And how long would such levels take, if the numbers were so large, to manifest themselves on the majority of women in the street where you live ?

Among the issues complicated by HO funded research is the offence itself. Andy Myhill and Jonathan Allen in their 2002 paper (http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/r159.pdf) refer to the fact that

around 60% of female rape victims did not see their experience as rape. Is this researchers re-defining rape to their own social norms ? The same overriding of the person concerned has been found in the US with 'petting' type behaviour was re-designated as alleged or actual 'campus rape'.

I would disagree that it has been either 'notorious' or 'difficult' to secure rape convictions, what is plain and has been accepted throughout history is that a charge of rape is an easy one to make but most difficult to defend.

The rape cases used in the article are aggregated and it would be wrong to think that any would lead to more convictions due to disproportionately more 'aggravated rape'. It is statistically not relevant in this article to differentiate. Those wrongly accused together with those rightly accused and those where there is aggravation can, and are, convicted.

It is this point - the wrongly accused - that should worry you. You should also be concerned that those wrongly convicted also serve longer prison terms than those who are guilty and who will be let out early only to do it again. (False allegations see Box A and Appendix 5: Tables 1 - 4 Attrition process - case outcomes for all reported cases' http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/hors293.pdf).

The article makes no particular argument but points out the present pitfalls and shortcomings. Therefore, I do not make any distinction between date rape, drunken rape, drug induced rape, 'simple rape', or any other subset of rape.

I am happy to concede the point that better evidence gathering could lead to higher conviction rates if the general public realises is made aware that (as HORS 'A gap or a Chasm' has had to), that a). False allegations are not rare, b) the conviction rate in England is not significantly different from other nations, e.g. Sweden, c). that England has had a unique increase in 'reported' rapes in the last 20 years which has yet to be explained.

The police are dong a very good job in what has become a highly politicised area of life (one has only to look at the directives, ministerial interventions and targets they now receive). As regards "negative mind" I think you it might be helpful if you were to read the staff and police comments (who daily deal with women who claim to have been raped) on pages 49-51 of A Gap or a Chasm".

(http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/hors293.pdf). These people are not idealists or crusaders fighting for a point of view but are doing their job.

Your comments deserved this fuller reply as I am sure many others hold similar views. Rape and false allegation thereof is a huge subject and the literature is very extensive. It is therefore difficult to adequately compress issues within it.

What should concern us all is the danger of slowly 'infantilising' women and the trivialising of rape which I warned the HO would happen, in 1999, if they continued on their chosen course. How can we reverse this trend ? I would like to see Lie Detectors adopted by the police - not to be used against an accused but to verify the story of the accuser.

Unfortunately, political thinking is not so enlightened and somewhat behind the research. IMO, the HO is hidebound and not just 'unfit for purpose' but of 'unmerchantable quality'. There is a mismatch between the law which reflects one era and young people who do not identify with that era.

On your final point, I would like to think I have had some influence on the HO or the establishment but I fear I have none. All the shortcomings are due to muddled thinking of people already in power who usually have not taken the time to adopt a balanced view of the subject and who, by now, IMO, should have moved on or retired, or realised their ideology was not working.

Robert Whiston.

snoozeofreason (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 26/10/2009 - 18:39

Not only is it wrong to say that the conviction rate for rape is 6.5%, it is also somewhat misleading even to say that the attrition rate is 6.5%.

Quoting the attrition rate this way can lead people to think that only 6.5% of reports of rape result in a conviction. In fact I have read many newspaper articles that say exactly this. It is however not true.

It is true to say that only 6.5% of reports result in a conviction for rape. However a report of rape can also result in a conviction for a lesser offence such as indecent assault.

A Home Office report available at

http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs07/rdsolr1807.pdf

found that when all convictions are included around 13% of reports resulted in a conviction.

This report was based on a sample of reports rather than on all reports, but the authors seem to have taken care to ensure that the sample was representative.

jon (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 27/10/2009 - 19:36

Heck of a great article. Lots of great facts and it certainly nails just about everything on the head. It's also great that you took some of the commenters to task and pointed them to the truth. I doubt they will take the time to actually read the report and be enlighted though.

Michael Lake (not verified) wrote,

Fri, 30/10/2009 - 03:11

As a technician and attempting to be an honest scientist, I learned from personal experience that non-technical people twist data to the point I no longer know what context they are using. Yet in law decisions are made about human lives based on such twisting of information. People attempting to be loyal to the truth are apparently the losers, regardless of what side they are on.

I fit the diagnosis of being an autistic savant, which resulted in claims I might be willing to rape and other sick untrue things said about be for the political gain of people who I did not know were against me. I am lucky that despite my lifelong developmental handicaps I also had the savant skills to eventually learn more of the truth and resist criminal conduct from other people.

Knowing that I can not trust authority any more than trusting strangers is the not what I was taught as a child. On the other hand, without trust no one wins.

Even after I became paralyzed there were people making claims about me which seemed more and more absurd but I really upset them by not being afraid in the way they expected. No amount of twisting facts will convince me to give up on logic and honest attempts scientific methods. Yes it makes me mad being a victim, but I refuse to play games in which I must give up on being honest.

yorksranter (not verified) wrote,

Sun, 20/12/2009 - 19:54

you know what Frank Furedi said about advocacy research

I'm guessing something along the lines of "Mmm, advocacy research! gimme more!"?

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 29/12/2009 - 01:38

Dear Yorksranter, If you want to contribute and not just post an opinion to this site it would be best if you first found out what Frank Furedi actually said rather than just guessing. This I urge you do and then a couple of cards will fall into place for you - and it wonlt be "gimme more!".

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 29/12/2009 - 02:31

Dear Snoozeofreason, Thank you for pointing out the complication to the attrition rate. Now that eth 6% figure has been knocked on the head by Baroness Stern it is time to move on.

The problem with the Home Office report, “Investigating and detecting recorded offences of rape”, (available at http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs07/rdsolr1807.pdf), is that it repeats much of what has been published before in several separate report booklets over the years.

What is new about it tends to be of a peripheral, non-consequential nature. The core problems remain.

It should concern us all that “the principal evidence” enabling an offence to be charged (see Table 4.3), was the victim’s own statement in 115 instances (equal to 73%) – not DNA or the examining doctor’s statement etc (figures based on 157 cases http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs07/rdsolr1807.pdf).

Investigating and detecting recorded offences of rape” still finds that lack of supporting evidence accounted for 45% of cases being dropped by the CPS and that the witness’s lack of credibility/unreliable accounted for a further 32%. In this regard facts have not changed much since 1985,

Most awkward of all to explain is that 'forensic analysis' accounted for 29% of cases being terminated by the CPS.

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Fri, 26/02/2010 - 13:33

Feb 26 2010 - Since the comments of Oct - Dec 2009, above, matters have moved on apace with Stern being appointed and now today's news from Woman's Hour (a staunch adherent to HO data) that a new report (from the Home Office ?) confirms that the conviction rate is around 50%. That is a big concession for WH - it's a pity the I-player is unaccountably "not available" as it would perhaps demonstrate how WH sails majesticoally on with its agenda quite unperturbed by the change.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 15/03/2010 - 21:18

Very interesting article, thanks (and surprisingly balanced given the general level of debate)

The 95% of rapes are unreported argument has always concerned me. It is regurgitated angrily as fact and one feels one will be shouted down if one questions it (as a male)

Another concern I have is this: is pressure being put on police to secure more convictions here (Harman was certainly trying to do so). Also I start to wonder if the authors of "A gap or a Chasm" were under pressure to produce certain conclusions.

This could become a self-fulfilling prophesy from start to finish. The unexplained rise in rape reports to the police is taken - alongside other dubious statistics - to be evidence that the police are mishandling rape claims. Therefore a clumsy, but very powerful kind of career pressure might be put on them and courts to secure more convictions - which will then be taken as evidence that there were more rapes happening all along.

Shame about any men wrongly sent to jail as a result. What do you think might happen to them several times in the years of their life spent in jail?

Mary (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 16/03/2010 - 21:11

And how long would such levels take, if the numbers were so large, to manifest themselves on the majority of women in the street where you live ?

This is the thing that always alarms me about discussions of rape. I'm a member of an all-women online community with 1000+ members. There's no agenda to the community, except that it's only for people who are women-identified, though it skews fairly middle-class. But given the number of women on that community who have discussed being raped, I have absolutely no difficulty believing something like the 2001 BCS data of 57 000 rapes or attempted rates a year, or things like one-in-six women. I was sixteen the first time a friend told me she'd been raped, and I've known a lot of other women who've talked about it since then. But people assume that if they knew someone who'd been raped they'd "know" about it, and if they don't know that anyone's been raped, then they don't know anyone who has been raped, ergo it must be a

Of course this is anecdata and not hard evidence, but there are people who argue that the only acceptable evidence that a rape has taken place is a conviction. There is no agreed methodology for determining the number of rapes (and I don't really understand how you are claiming to be able to quantify the number of false allegations here - how could you be any more certain that a rape allegation is false than you could be certain that it is true? Retraction doesn't do it for me, sorry.)

In that situation, how on earth can you even begin to talk about the number of punishments in relation to the number of crimes? It becomes an impossible conversation.

Mary (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 16/03/2010 - 21:12

sorry, missing end of first paragraph - "ergo it must be a wild exaggeration".

An Non (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 03/04/2010 - 15:22

Rape is a horrible crime. False Accusations of Rape are also horrible crimes.

The issue of false rape claims is discussed in detail at: http://falserapesociety.blogspot.com

For a primer:

http://falserapearchives.blogspot.com/2010/01/false-rape-primer.html

Men and Women both are victims of false accusations. It is a civil and human rights issue.

Note: This article has been cited by a commentator on http://falserapesociety.blogspot.com 3 Apr 2010.

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 29/07/2010 - 00:06

It used to be very fashionable, 10 or 12 years ago, for some leading American feminists to claim to have been victims of domestic violence or abused as a child. They would often accuse their husband of perpetrating it. Perhas it gave them some sort of credibilty with their target audience ?

Some years later they recanted and I can't recall how they excused themselves but it put me in mind of Hilary Clinton's famous "mis-spoke" whn she claimed to have come under sniper fire during her 1996 trip to Bosnia.

Hilary (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 20/11/2010 - 19:40

False reporting of rape crimes in the UK stands at 3% which is the same as any other crime.

The comments on here are comparable to those on a Daily Mail report.

Attrition in rape crime is relevant because victims of rape are more likely to be harassed into withdrawing charges. That is hardly surprising when the term 'rape' is changed to 'non consensual sex'.

Rape and sex are not comparable. I know that from experience. The police and courts are doing a mediocre job. At best.