What random Mandatory Drug Testing reveals about methadone prescribing for prisoners

Recent parliamentary answers to astute questions from Andrew Pelling MP have provided a means of assessing the progress of the Prison Service’s Integrated Drug Treatment System (IDTS).

In yesterday’s article I described my difficulties in obtaining and making better use of the data gathered in prisons. Today I will explore the answers given to Mr Pelling, as an exercise in statistical detection, and see what conclusions can be drawn.

The IDTS was announced in July 2006 as a joint initiative from HM Prisons Service and the NHS. Clinical drug services in prisons had been under-resourced, with poor links between assessment, counselling, referral, advice and through-care services, said the letter from John Boyington, Director of Health and Offender Partnerships, announcing its launch.

The aim of IDTS was to increase the volume and quality of treatment available to prisoners,particularly substitute prescribing, Mr Boyington promised. It is not, of course, just about methadone substitution - it includes clinical and psychosocial elements too.

Nor is the initiation of IDTS necessarily straightforward either for prisons or for National Health Service commissioners. There is a central project team from the DH/National Treatment Agency which manages the first and subsequent waves of IDTS and receives quarterly monitoring reports which do not appear to include information from random mandatory drug tests (rMDTs).

In March 2009, Edward Garnier QC MP asked how successfully IDTS had been implemented, when, and in which prisons. David Hanson’s parliamentary answer identified the 17 first-wave prisons with full IDTS funding from 2006/07.

In alphabetical order, they are: Birmingham, Bullingdon, Doncaster, Dorchester, Eastwood Park, Featherstone, Foston Hall, Gloucester, High Down (in Andrew Pelling’s constituency), Hull, Low Newton, Moorland (closed & open prisons), Nottingham, Ranby, Styal, and Wormwood Scrubs. Eleven prisons, to which I shall refer as IDTS Tier 2 prisons, had the psychosocial elements of IDTS added in 2007/08 when the clinical element had begun in either 2006/07 or 2007/08, namely: Ashwell, Bristol, Brixton, Durham, Edmonds Hill, Elmley, Everthorpe, Highpoint, Guys Marsh, Lindholme, and Wealstun. The remaining prisons - hereafter, the rest - may (or may not) have embarked even on the clinical elements of IDTS by 2008/09.

Andrew Pelling’s questions in July 2009 asked about the performance of mandatory drug testing. First, he asked for the results of rMDT versus targeted testing (tMDT) per prison by financial year (2002/03 to 2008/09) in detecting prisoners who were positive for specific drugs.

Prescribed methadone was included among the specific drugs so that, from the answers provided, an informed analysis could reveal how methadone substitution therapy had been rolled out during 2006/07 to 2008/09 in the first wave of IDTS prisons, and by 2008/09 in Tier 2 IDTS prisons.

Based on the same prisons’ rMDT results for the preceding two financial years of 2004/05+2005/06, a judgement could also be made about: (a) how representative the initially-selected IDTS prisons were, and (b) IDTS prisons’ likely opiate positive rate in rMDT in 2008/09 in the absence of methadone substitution.

Now, by assuming that the vast majority of those receiving methadone substitution would otherwise have been using heroin in prison, of whom an estimated one in 3.5 would have tested positive for opiates in rMDT, (see yesterday’s article), the IDTS prisons’ “likely opiate positive rate in rMDT but for methadone substitution” can be proposed as: “Opiate positive rate in rMDT + one third of Prescribed Methadone positive rate in rMDT”.

Andrew Pelling MP also asked about the costs of rMDT, on which there was apparent ministerial ignorance.

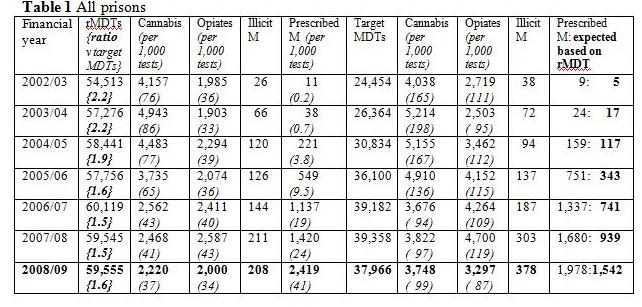

Table 1 shows that the number of MDTs in prisons in England and Wales increased from 79,000 in 2002/03 to 97,500 (nearest 500) in 2008/09. Over the period, the ratio of rMDT:tMDT has reduced from 2.2:1 to 1.6:1 by dint, primarily, of an increase in the number of tMDTs from 24,500 to 38,000 while the number of rMDTs has remained in the range of 54,500 and 60,000.

From Table 1, notice that the opiate positive rate in rMDT fluctuated markedly from year to year even before the introduction of IDTS: a difference of 3 per 1,000 is very highly significant when denominators are 54,500 to 60,000 rMDTs and the opiate positive rate is of the order of 40 per 1,000. The annual cannabis positive rate in rMDT also fluctuated markedly but a dramatic fall has occurred since 2005/06. Year-on-year positive rates for cannabis and opiates were two to three times higher in tMDT than in rMDT.

From 2004/05, an adjusted opiate positive rate per 1,000 rMDTs, approximated as “Opiate positive rate in rMDT + one third of Prescribed Methadone positive rate in rMDT” works out as 41 in 2004/05, 39 in 2005/06, 46 in 2006/07, 51 in 2007/08 and 47 in 2008/09.

The final column of Table 1, in bold face, is a count of the numbers of tMDT clients whom we would expect to test positive for prescribed methadone – on the assumption that selection for tMDT is independent of whether an inmate was in receipt of prescribed methadone. From 2004/05, the actual numbers positive for prescribed methadone in tMDT greatly exceed their expectation.

This means either that prisons specifically targeted for testing-on-suspicion those inmates in receipt of methadone maintenance or that prisoners receiving substitution therapy were complicit in the use/supply of illegal drugs in prison or both. Whereas twice as many tMDT testees were positive for prescribed methadone as were expected on a prevalence-basis in 2005/06 and 2006/07, the excess - although still clearly evident – reduced to under 30% by 2008/09 (actual = 1,978; expected on rMDT-basis =1,542).

Now let’s turn to the integrated drug treatment system (IDTS) and see if the data made available by the parliamentary answers provide a measure of how effectively IDTS is being introduced. My criterion for judging this will be the degree to which methadone substitution has occurred.

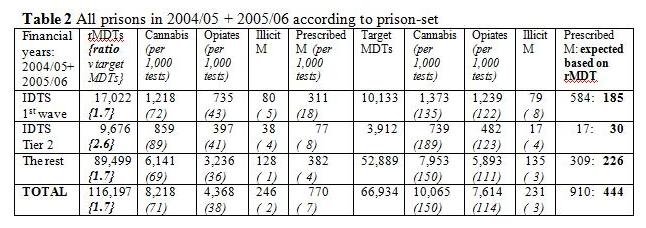

Table 2 shows that the first wave of IDTS prisons was non-randomly selected: they had a pre-existing higher rate of methadone prescribing in 2004/05+2005/06 than either the Tier 2 or remaining prisons. Moreover, in contrast to the rest of the prisons, those in IDTS’s first wave or in Tier 2 were selected pragmatically on the basis of their generally higher opiate rate in rMDTs.

The first wave and Tier 2 prisons differ from each other in terms of their ratio of rMDT: tMDT (1.7 for the first wave but 2.6 for Tier 2 prisons), their cannabis positive rate (72 per 1,000 rMDTs for the first wave but 89 for Tier 2 prisons) and in the extent to which on-suspicion testing targets those in receipt of methadone substitution. Pre-existing rate of methadone prescribing was also twice as high in the first wave of IDTS prisons (at 18 per 1,000 rMDTs) as in Tier 2 prisons.

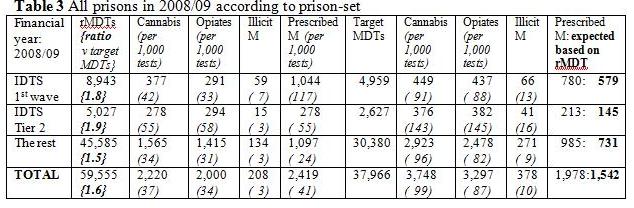

Table 3 shows that, by 2008/09, 12 per cent of inmates in the first wave of IDTS prisons were receiving prescribed methadone but the proportion was barely 6 per cent in Tier 2 prisons (95 per cent CI: 4.9 per cent to 6.2 per cent) as compared with 2.4 per cent in the remainder of prisons.

Prior to the roll-out of IDTS, the opiate positive rate in 2004/05+2005/06 was similar in the IDTS first wave (4.3 per cent with 95% CI:4.0 to 4.6 per cent) and Tier 2 prisons (4.1 per cent with 95% CI: 3.7 to 4.5 per cent), but their opiate rates had diverged strikingly by 2008/09 to be 3.3 per cent (CI: 2.9 to 3.6 per cent) and 5.8 per cent (CI: 5.2 to 6.5 per cent) respectively.

However, the adjusted opiate positive rate in rMDTs in 2008/09, approximated as “Opiate positive rate in rMDT + one third of Prescribed Methadone positive rate in rMDT” works out at 71 and 77 per 1,000 rMDTs (that is: 7.1 per cent and 7.7 per cent) in the IDTS first wave and Tier 2 prisons respectively.

Just as the unadjusted opiate positive rMDT rates had diverged, there is corroboration in the increase in IDTS prisons’ adjusted rates per 1,000 rMDTs (from 49 and 44 in 2004/05+2005/06) to 71 and 77 in 2008/09 to suggest that IDTS may have been introduced to prisons at a time when availability of illicit opiates among inmates was otherwise increasing.

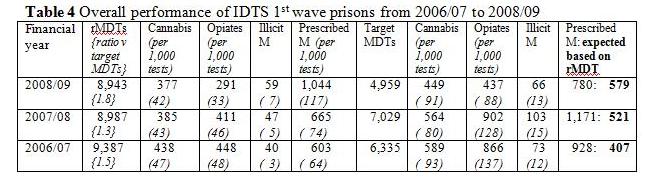

Table 4 documents how very gradual was the roll-out of prescribed methadone in the first wave of IDTS-funded prisons, with only 6.4 per cent and 7.4 per cent of inmates receiving methadone substitution in 2006/07 and 2007/08. The disparity in prescribed methadone in 2008/09 between the first wave of IDTS prisons and Tier 2 is thus hardly surprising as it is consistent with the performance of the IDTS first wave prisons in their initial two years.

The final column of Table 4 makes clear that more than twice as many inmates who received methadone substitution were subject to tMDT in 2006/07 and 2007/08 than were expected on prevalence alone – a phenomenon that relaxed considerably in 2008/09, by which time the prisons may have learned that such targeting did not improve their index of suspicion for illicit heroin.

However, the good news is that IDTS prisons have succeeded in rolling out prescribed methadone without proportionate increases in the positive rate for illicit methadone in rMDTs. Only modest increases have occurred between 2004/05+2005/06 and 2008/09 - such as from 5 to 7 per 1,000 rMDTs in the first wave of IDTS prisons when the prevalence of prescribed methadone increased from 18 to 117 per 1,000 rMDTs.

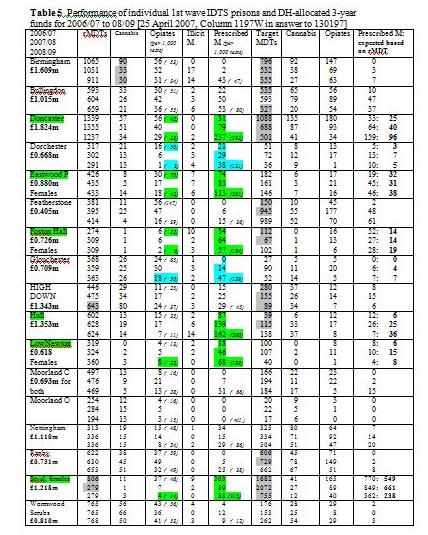

Table 5 illustrates considerable differences between the performance of individual IDTS first wave prisons. In particular, only six of the 17 individual prisons were prescribing methadone to at least 15 per cent of inmates (highlighted in green - Doncaster, Eastwood Park, Foston Hall, Hull, Low Newton and Styal Prison, where the proportion was highest at 33 per cent) with two other prisons (Dorchester and Glouchester) having achieved 10 per cent by 2008/09.

Conclusion: rMDT has revealed the slow pace of implementation of methadone substitution in the first wave of IDTS prisons. In only six of 17 prisons was methadone prescribed for at least 15 per cent of inmates. The roll-out of IDTS has been achieved without a proportionate increase in the rMDT positive rate for illicit methadone, but seems to have occurred against an otherwise rising background, or adjusted, rate of inside-use of opiates.

Further parliamentary questions may be needed to probe why IDTS-funding has been insufficient to guarantee the intended health services for prisoners. Although a central project team receives quarterly monitoring reports, even such limited statistics on the performance of IDTS-funded prisons, as here, have not been aired publicly. Relevant commissioners may have to look to their laurels, and better assist prisons in their delivery of IDTS to prisoners.