Whiling away the hours in A&E

Want to know how long you’ll have to wait in your local A&E? The NHS Information centre today published a report that uses Hospital Episode Statistics to compare how different trusts perform.

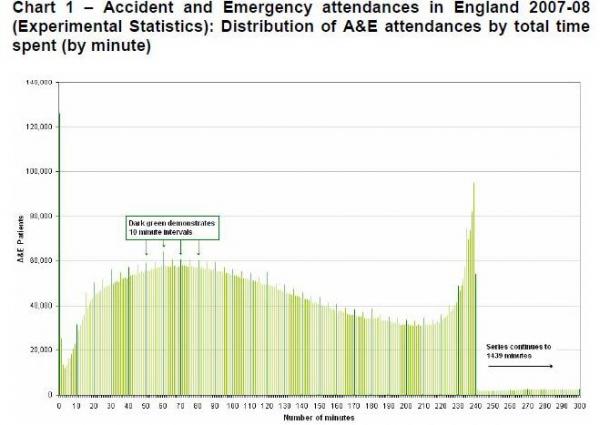

Previous studies have shown that the four-hour target – within which patients have to be seen, and admitted or discharged – tends to cause bunching as the end of the four-hour window approaches. Typically, 6 per cent of patients are dealt with in the last ten minutes, and there is a surge of admissions close to the four-hour limit. But in nine trusts, the figures show, 9 per cent or more of patients wait until the last ten minutes to be treated.

Chart 1 (below) shows the national picture for England in 2007-08, from the IC's report. The spike at zero minutes is accounted for by patients who pass through A&E to be immediately admitted, plus some data quality issues. The large spike close to four hours speaks for itself.

But trusts differ, the report shows. Some run such efficient A&E departments that most patients are dealt with quickly, and very few wait longer than three hours. There is no desperate surge as the deadline approaches. Others deal with patients steadily, but not sufficiently quickly, and are forced to squeeze a substantial proportion into the last ten minutes.

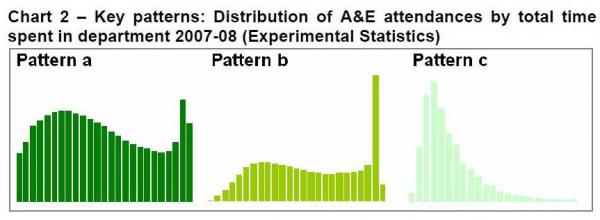

Chart 2 shows the national pattern (a), compared to two other patterns that are observed. In pattern b, fewer patients are dealt with and there is a rush at the end, and pattern c, the ideal, a distribution curve that shows no influence of the four-hour target.

Of those patients who are dealt with in the last ten minutes, admissions are high, as one might expect. If patients are being kept under observation in A&E because medical staff are uncertain whether to admit or not, they are likely to err on the side of caution as decision time approaches. Better to admit them than take the risk of discharging them in a vulnerable state, or of breaching the four-hour target.

This may have had the effect of increasing admissions through A&E, which have been rising in recent years. There has also been a rising trend in next-day discharges, which would be consistent with this conclusion. Another possibility is that trusts are “gaming” the system because admitting a patient, even for a single night, earns them more under payment by results than treating the patient in A&E.

However, that's guesswork. The report is not designed to address that point, but it does show in an elegant way how a target designed to ease the lengthy waits in A&E can have a distorting effect.

The Chief Executive of the Information centre, Tim Straughan, urged A&E departments to compare how their approach differs from others, as there are marked differences from place to place. The report include a trust-by-trust breakdown to make this possible.

Mike O’Brien, the health minister, claimed that the report showed the “overwhelming majority” of patients were seen within three hours. Actually, the figure is 73 per cent, which is certainly a comfortable majority - if not perhaps an overwhelming one.

Thomas Moore (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 04/11/2010 - 17:16

I am currently a student at Swansea Metropolitan University, in my final year of studying for a BA(Hons) in Product Design.

For part of my degree I have to complete a Major Project. I am extremely interested in exploring ways in which the patient experience of A&E may be enhanced. I have been undertaking various types of preliminary research to get a better understanding of the issues involved.

I have come across your report online and have found it very interesting, if you have any information i can use for my major project i would be very grateful.

Any help that can provide will be very much appreciated.