Coroners’ conduct of inquests into UK military fatalities in Afghanistan and Iraq

The lengthy delays endured by military families waiting for inquests into soldiers killed in Afghanistan and Iraq have been detailed here before.

An analysis of more recent data shows that delays declined in 2008 and 2009, even though military deaths increased. The decline corresponded with an increase in the numbers of coroners taking such inquests. While it is good that delays have been reduced, there may be a danger that coroners with limited experience of military inquests are insuffiently aware of the evidence given in other inquests to do the best possible job.

In the earliest phase of UK’s military deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq (2002 to 30 April 2006), 111 UK military deaths were subject to, or taken into account at, coroners’ inquests. The military families concerned experienced unduly long waiting times to inquest verdict, often because inquests were delayed to await the report of a military Board of Inquiry.

These 111 inquests were conducted by just 12 coroners, seven of whom presided over a single inquest but five accumulated considerable experience by dint of presiding at six (Sir RC), 16 (DM), 20 (SL), 27 (AW) and 35 (NG) respectively. Thus, 104 out of 111 inquests were conducted by experienced coroners: that is coroners who, in the period concerned, presided at the inquest into more than five military deaths.

A further 60 military fatalities occurred from 1 May to 31 December 2006: AW conducted the inquest for 53, SL for two, and five other coroners conducted single inquests.

In 2007, which saw 88 military deaths in Afghanistan and Iraq, there was a change in how inquests were assigned, with more coroners becoming involved. In that year, 24 coroners each presided over a single military inquest, seven took two, and only three – AW (6), ACo (8) and DM (36) – took more than five. Thus, in 2007, 50 out of 88 inquests (57 per cent) were conducted by these three ‘2007-experienced’ coroners.

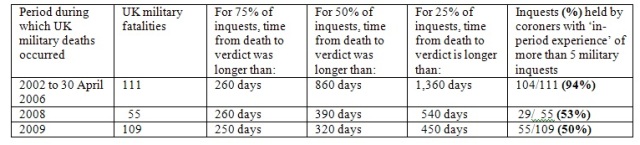

The Table contrasts the initial period up to 30 April 2006 with military fatalities in the calendar years 2008 and 2009. In the initial period, waiting times to inquest verdict were overlong and the burden fell on few coroners. By 2008 (55 UK military fatalities) and 2009 (109 UK military fatalities), the changes made meant that median waiting time had reduced from 860 days through 390 days to 320 days in 2009 despite the number of military fatalities having doubled between 2008 and 2009.

For 2008 fatalities, DM conducted 18 inquests and DR 11 with 18 coroners each presiding over a single inquest, two at pairs of inquests and SMcG at four. In 2008, 29 out of 55 inquests (53 per cent) were thus conducted by three ‘2008-experienced’ coroners. For 2009 fatalities, DR conducted or was assigned 47 inquests and ACo eight with 29 coroners presiding over a single inquest, eight others over pairs of inquests, IA at four and DM at five so that 55/109 inquests (50 per cent) were conducted by two ‘2009-experienced’ coroners.

Battlefield tactics can change quite rapidly so that coroners’ relevant experience is best measured by having conducted inquests into contemporary military fatalities.

I am requesting copies of the verdict and summing-up by coroners at the inquests into the eight hostile deaths (most by improvised explosive devices) in Afghanistan of presumed Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) personnel for whom inquests have concluded. These are, so far as I can ascertain: Warrant Officer 2 O’Donnell, Captain Shepherd, Staff Sergeant Schmidt, Sapper Watson, Captain Read, Warrant Officer 2 Markland, Sapper Mellors, and Sergeant Fox. The eight inquests were presided over by five different coroners, Dr Emma Carlyon having presided at three and Sean McGovern at two.

Did Dr Carlyon, now the most experienced, need to acquaint herself (as I seek to do by my requests) with key evidence that was heard in the previous two inquests? Are military families, and their legal representatives, able to study, and learn from, preceding relevant inquests?

So far, despite evidence of bona fides, Dr. Carlyon has not given me the right of inspection as “a properly interested person to inspect such report, notes of evidence, or document”. But she is willing to change her decision if I can cite precedent, invoke authority from the Ministry of Justice, or – in the case of any forthcoming inquests into the deaths of EOD personnel that have been assigned to the coroner’s court in Truro – attend in person.

In 2008, I published a review of fatal accident inquiries (FAIs) into 97 prisoner-deaths in Scottish prison custody over a 5-year period. Forty-two sheriffs had made written determinations, accessed by Freedom of Information requests which their clerks responded to with remarkably efficiency. Many of the recommendations from that review have since been reflected in the Lord Cullen’s Inquiry into the conduct, reporting and statistical oversight of Scotland’s FAIs.

My concern is that if Coroners in England make a narrative verdict, others with a legitimate interest may not see it. A coroner's verdict represents a summary of the evidence and ought to be a matter of written record. But as my exchange of correspondence with Dr Carlyon shows, this is not necessarily the case.

Access is important not only for fellow coroners, especially as many may conduct only one or a pair of inquests into contemporary UK military deaths in Afghanistan, but also for other interested parties, most notably other military families and their representatives.

Henry (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 29/03/2011 - 12:32

This is one of my favourite sites. However:

"While I await information from Dr Carlyon and others, I worry that if England’s coroners make a narrative verdict, the possibility is left open that this important summing-up by them of the evidence heard which underscores the coroner’s determination is not a matter of written record."

....

Que??

confused.person (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 30/03/2011 - 09:19

I read this but am now not clear whether the writer is proposing that it's better to have the families suffer longer delays or have less military-fatality experienced coroners share the burden? It seems to me that there is a natural trade off here.

What is the variation in the inquests presided over by the less experienced coroners conducted so far that is causing concern?

Nigel Hawkes (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 30/03/2011 - 14:07

An updated and I hope clearer version is now on line

David Hartley (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 30/03/2011 - 19:05

When the incoming flights were moved from Brize Norton to Lyneham in 2007, the official reason was to allow the aircraft parking area at Brize Norton to be redeveloped. However, an immediate consequence of the change was also to remove the bodies from the jurisdiction of one Oxfordshire deputy assistant coroner, Andrew Walker, who had delivered several verdicts deeply critical of the government and armed forces of both Britain and the US. See, for instance, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6326193.stm

In June 2007, Mr Walker’s fixed-term contract as an Oxfordshire coroner was not renewed. Personally, I’m not one for conspiracy theories, at least where there is no more than suspicion to support them; however, Mr Walker’s extended conflict with the British and US governments may well have delayed the resolution of several inquests. I think he deserves our gratitude for this: better to push for the truth than to reach a premature verdict which glosses over politically inconvenient problems.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 02/04/2011 - 01:53

It is no part of the Coroner's remit to be divisive or political. Occasionally I have been startled by their alleged opinions as reported in the press.

I am staggered to read that it can take 800 days to get a post mortem concluded. My elderly mother dies in January of this year - waiting 800 days to bury her wouild be intolerable.

Forgive my naivety but what is so 'tricky' or complex about a military death ? Being blown in by a ruptured gas main or shot during a robbery results in similar injuries, do they not ?

if I am totally wrong and such expertise is vitally needed but in short supply, then with budget cuts in the US couldn't we attract US practioners to the UK on short service contracts ?