How many children are murdered in Britain every year?

Sharon Shoesmith, Haringey’s former Director of Children’s Services last week gave evidence before the parliamentary Education Committee. In the process she re-ignited the basic unanswered question "Exactly how many children are murdered in Britain every year? "

It seems a reasonable enough and straightforward question, but in Britain it is one with no definitive answer, each answer offered being compromised by exemptions and caveats.

No single government department, it would appear, keeps a comprehensive record. Those Whitehall departments that do keep a record of tragic child deaths from unnatural causes - child abuse, maltreatment, murder etc - use different methodologies and thus the annual totals they produce are at variance with one another.

In broad outline, the available statistics from departments and child-focussed agencies fall into three groups each hovering at different levels for child deaths caused by abuse: around 50-60 a year, 100+ a year, or more than 200 a year. These discrepancies are very large.

If nothing else, Sharon Shoesmith’s testimony confirms the impression outsiders hold of duplication by Whitehall and its institutions in not even agreeing a common figure. From public pariah after the death of Baby P, she has emerged as a doughty fighter whose determination not to be scapegoated may actually help to trigger a reappraisal of the whole system - Lord Laming’s highly critical report notwithstanding.

She makes a valid point when she describes the abuse heaped upon her and Haringey as depending entirely on a simplistic ‘narrative’. We can all see that Peter Connelly did not die because Haringey was uniquely weak but because the adults around him were monsters. It was they who tortured the little boy to death – no one else. The call to sack everyone from the director down to the social workers involved was pointless.

When any corporation or company expands to over 1,000 employees it is impossible for the CEO to know what is going on in every office and what is contained in every file. Ms Shoesmith had around 1,300 staff, including about 500 social care staff, and in addition the burden was increased by the need to liaise with other institutions, including the police, the NHS, the probation service, youth offending institutions, and so on.

There seems to be two quite distinct question and neither is being answered in the current debate. One is what going on inside the head of some of the people who kill children, and the second is the total so killed.

All over the country Children Services and Social Services face the same problems. As early as October 2002 ministers’ attention was drawn to the chaotic child protection system in a joint chief inspectors’ report Safeguarding Children, its conclusions summarised in The Independent as a “chaotic child protection system that is under-funded, under-staffed and too far down the Government's list of priorities . . . the continual turnover of staff [ meant that ] children had lost confidence in the whole system.”

In her testimony Sharon Shoesmith told the committee that in the year that Peter died (2007), 54 other children also died. In the first 10 months of 2009, 56 children died. From this we can assume the total for 2010 will be in the same region. Shoesmith also told the committee that in the “decade 1999 to 2009, 539 children died in this way” (by parental or adult abuse/neglect).

Given the discrepancy in official child death totals one wonders which source she used and whether the committee members were fully aware of the discrepancies in the recording of child deaths that riddle the system.

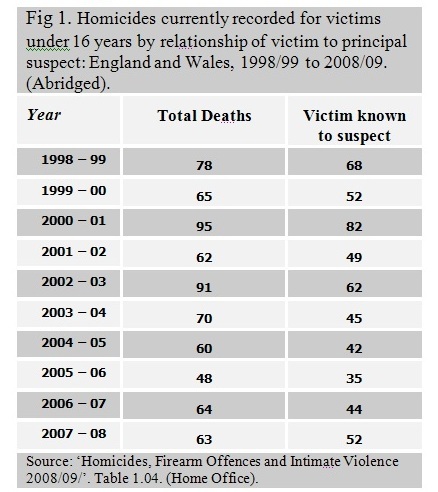

Anyone looking into the topic for the first time would rightly assume that they could rely on Criminal Statistics, published by Home Office. Fig 1 (abridged from the original) shows the total from this source to have been 50-60 a year in recent years, roughly in line with Sharon Shoesmith’s evidence The Total Deaths column includes deaths caused by a stranger or where no suspect is known.

However, some analysts in the child abuse industry think a truer total may be double that – 100 a year, or maybe more. That was the figure quoted for the UK in a UNICEF report in 2003.

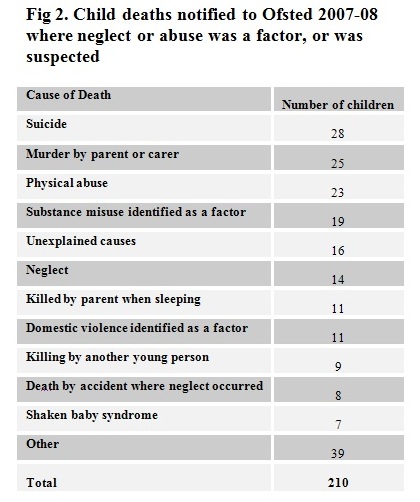

One comparatively recent addition to the many Whitehall departments all with an interest in children’s deaths, Ofsted, believes child deaths to be higher still, in the region of 200 per year. Fig 2 details the child deaths recorded by Ofsted in 2007-08 together with causes.

What is notable here, compared for example with US data, is the lack of any deeper analysis, The unspoken questions are what age and what sex are the victims and what age and sex are the ‘perpetrators’? Where a specific category is given, e.g. 25 children confirmed as being murdered by a parent in 2007-08, we have no idea if it was by a mother, or a father, or a step parent. British statistics are recalcitrant in never drawing these crucial threads together.

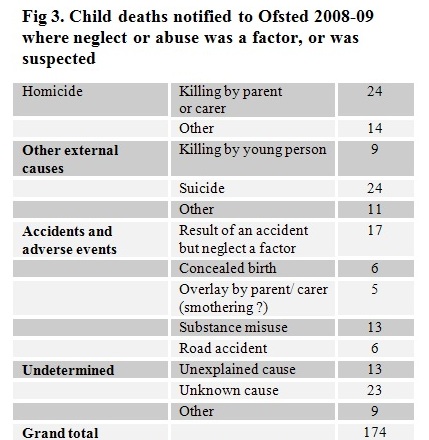

By the following year, Ofsted had changed the way it categorised child deaths (Fig 3) making comparisons difficult. The underlying problem with Ofsted data is that it relies on “serious incidents involving children who have been abused/died of abuse in the last 24 months” being forwarded by local authorities. If no reports are sent by local authorities Ofsted is forced to list no murders that year.

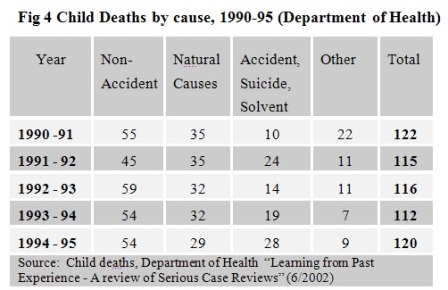

As if to not to be left out of contention, the Department of Health compiles it own figures for child deaths (Fig 4).

But its data is not always easy to follow or compatible with others sources. Fig 4 (above), shows how the Department of Health analysed child deaths in the first half of the 1990s, taken from data from serious case reviews. It is perhaps astonishing to learn that throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century there existed variations in practice between the various Area Child Protection Committees (ACPCs) in how they respond to a reported child death.

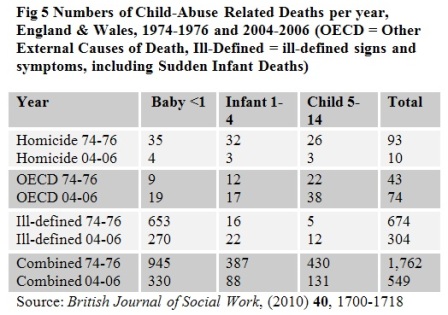

Finally there are data that appeared in a study published last year in the British Journal of Social Work by Colin Pritchard and Richard Williams. They do not cite a source but published the following table (abridged here) which compares deaths in 1974-76 with those in 2004-06.

Their total is 549 abuse-related deaths a year in recent years, much higher than figures from other sources because it includes categories that may or may not be abuse-related.

But it also shows a dramatic drop in numbers since the 1970s. The authors compare the figures to nine other major developed countries and conclude that child deaths related to abuse have fallen faster in England & Wales than in most similar countries – a fall in the overall total by 66 per cent in 30 years, or 76 per cent when measured as a number per million population.

These child deaths have also fallen faster than have all causes of death, which show a 67 per cent decline over the same period, measured per million population. They place England & Wales the second lowest of the ten countries for child-abuse related deaths, bettered only by Italy.

Their conclusion drawn is that the much-criticised child protection services have actually done a better job than they are generally credited with. An alternative explanation might be that parents in England & Wales have become less violent and abusive towards their children at a rate not matched elsewhere.

The authors remark: “The extent of the improvements, especially in England & Wales, may be surprising, as the media imply that matters have never been worse”.

Can Parliament reach any competent judgment or formulate any worthwhile policy when

the numbers disagree so widely? The basis of any sensible policy has to be agreement on the actual size of the problem which, as we have seen, is as remote as ever.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 03/02/2011 - 09:37

have you got any results for 2010?