Misdirected benefits fail to cut winter deaths

The pensioners’ winter fuel payment - £250 per household, no means test, no questions asked - drops into the bank accounts of those over 60 during December.

It comes in handy for buying the grandchildren their Christmas presents, but appears to have very little effect in reducing deaths or helping those who cannot afford to heat their homes, its original purpose.

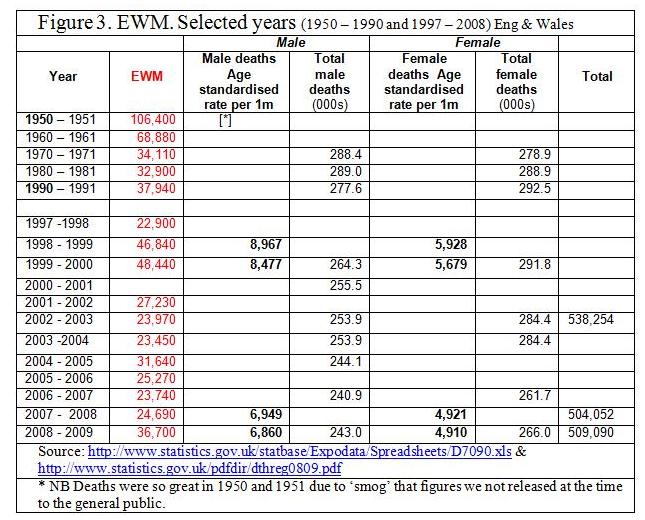

Last month the ONS published figures for Excess Winter Mortality (EWM) for 2008-09, which showed the highest number of excess deaths (36,700) since the winter of 1999-2000. There were 15,300 extra deaths in men and 21,400 in women.

This represented an increase of 49 per cent over 2007-08, the ONS reported. Broken down by age, there were 7,300 excess deaths in those under 75, and 29,400 among those aged over 75. EWM is calculated by defining the winter as December to March, counting the numbers of deaths in that period, and comparing them with the previous August to November and following April to July. EWM is then the difference between winter deaths and average non-winter deaths.

One reason why more women than men die during the winter is simply that there are more of them in the age groups at greatest risk. More than three times as many women as men survive past 80. In 2008-09, according to the provisional figures (read off from Figure 4 in the ONS bulletin) about 6,000 excess deaths were recorded in men over 85, and about twice as many in women of the same age.

However, given the actual numbers of men and women in the age group, the actual risks of death are greater for men. ONS figures show that the death rate per million in 2008-09 was 6,860 for men, and 4,910 for women

Winter fuel payments were introduced in the winter of 1997-98, and extended in 2000-2001. The aim was to reduce “fuel poverty” (defined as a household needing to spend more than 10 per cent of income to achieve at temperature of 21C in the living room and 18C elsewhere for nine hours a day in the week and 16 hours a day at weekends.) Since 2000, the Audit Commission reported recently, the programme has cost over £20 billion. Annual costs now run at £2.7 billion.

This may well be one of the worst-targeted and least effective benefits ever devised. Only 12 per cent of those who qualify for fuel payments are in fuel poverty (Audit Commission), and of those who get it, 400,000 are higher-rate taxpayers. For them, a tax-free £250 is a worthwhile Christmas bonus. But it has little to do with alleviating poverty or reducing EWM.

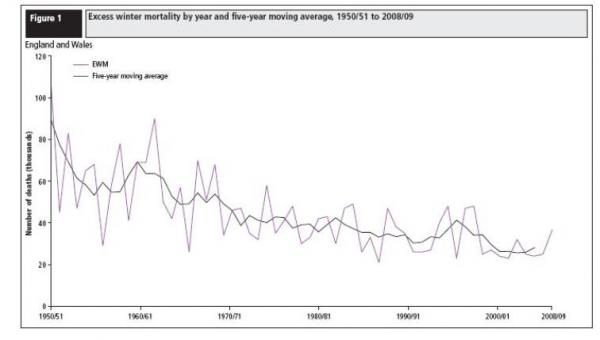

The belief energetically propounded in the 1990s was the reducing fuel poverty would cut the number of winter deaths, but recent data hardly suggests any such effect. EWM has fallen steadily since the 50s but the affect of winter fuel payments is imperceptible (Figure 1, below, comes from the ONS bulletin).

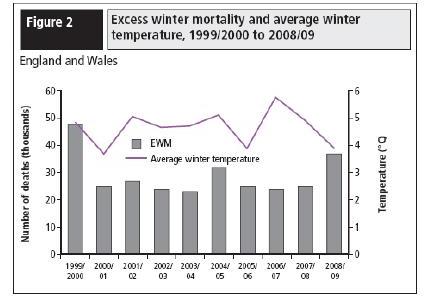

Defenders of the payment might argue that the rise in EWM in 2008-09 was in part caused by rising levels of fuel poverty as fuel prices rose sharply. But in fact there does not appear to have been any clear link between EWM and average winter temperatures since 2004-05.(fig 2, below)

One might speculate that the method of payment used for cold winter payments may be the culprit. There is no obligation to spend the money on fuel. An alternative method might involve a “credit” for gas and electricity with the utility companies involved, or if that were to prove too complex, a simple waiving of all utility bills for December and January but with no possibility of a claw back in the following months.

But a payment for all pensioners to relieve a problem suffered by only 12 per cent of them is hard to defend: the Audit Commission said the system was “unsustainable” and the money would be better spent lagging, insulating, reglazing and modernising the homes of pensioners, which would have the additional benefit of reducing carbon emissions.

Teasing out data from the ONS files has its problems. Many separate inquiries have to be made to get an historical trend, many lead to dead ends, blank results, and in some instances the measuring tool varies. Figure 3, replete with gaps, epitomises the problems an occasional interrogator comes face to face with when hunting data for a customised comparison.

The top section gives deaths at the beginning of each decade beginning in 1950, when smog was a serous killer, through to 1990. Significant gains can be seen as EWM deaths fall in those 40 years. No perceptible trend is visible in recent years: 1998 to 2000 saw an increase in EWM, followed by a rapid decline and an equally rapid increase to last winter’s high figure.

If this data had been more easily accessible it might have added to our understanding but the amount of information that was compatible (and comparable) for the various years was very sparse and or too difficult to locate, as the table reveals.

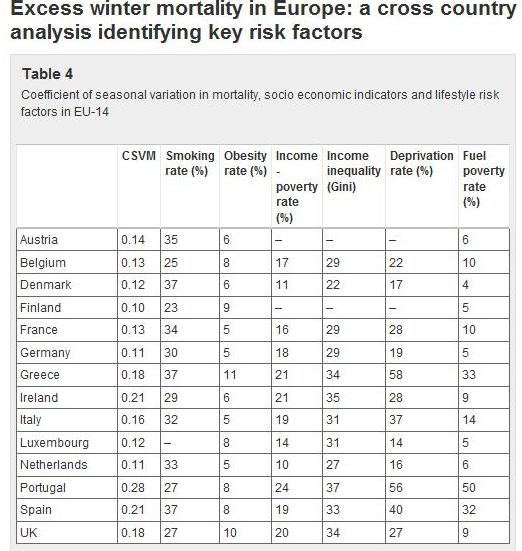

Studies have shown that EWM is found everywhere, and is correlated with inequality, poor insulation standards, spending on public health, deprivation, and fuel poverty. A cross-country study by Dr J.D. Healy of University College Dublin, published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health in 2003, compared 14 EU countries.

The results, summarised in Table 4 (below) show less of a clear-cut relationship with fuel poverty than might be expected. The excess mortality in this table is expressed a coefficient, constructed by dividing the excess winter deaths by average summer deaths. The highest coefficients were found in Portugal, Spain and Ireland, but the data may now be out of date: the period covered was 1988 to 1997.

Clearly EWM is a complex problem with links to many socioeconomic variables, but fuel poverty does not stand out as especially important. Given that, and the way the benefit has been so ineptly targeted, it is hardly surprising that winter fuel payments to pensioners have failed to have much effect. Once given, however, such benefits are almost impossible to take away.

David Laraman (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 21/12/2009 - 09:09

The comment that the payment is £500 where both partners in a household are pensioners in their own right is incorrect. In such circumstances each receive £125.

Paul Spicker (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 22/12/2009 - 12:16

There are two key assumptions in this critique. The central assumption is that helping people with fuel bills is supposed to reduce winter deaths. When Malcolm Wicks, now representing the government on energy issues, reviewed the evidence in the 1970s, he found that hypothermia was largely unrelated to heating systems; the primary causes of hypothermia were the physiological health of old people, related e.g. to nutrition. Hypothermia occurred not because heating was low, but because some frail older poeple were unable to maintain their body temperatures in environments where others in good health were able to do so. Despite that finding, Wicks concluded that more support should be available for fuel. The source is M Wicks, Old and cold: hypothermia and social policy, Heinemann 1978.

The other assumption is that benefits are only targeted and used effectively when they focus on the poorest. The principles behind income maintenace in the UK are much more complex. One aim is social protection - providing insurance for people in certain social contingencies. The purpose is to avoid interruptions in the flow of income flow or problems associated with unexpected liabilities. A second aim is "income smoothing", transferring income across the life cycle. Third, there is the response to need - not just the relief of poverty. We don't demand that people with disabilities have to be poor before they merit specialised support; nor do we make that demand of older people.

Nigel Hawkes (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 28/12/2009 - 16:53

David Laraman is right. I've corrected this point.

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 28/12/2009 - 17:18

Dear Mr. Spicker,

Thank you for making some valuable and valid points.

You question whether it was ever believed that the winter fuel payment would prove effective in cutting EWM. If that is true, then why have governments persisted with it ? And what should replace it?

When you write of the misconception that benefits are best 'targeted' at the poorest, have you in mind the New Zealand experience of trying to target benefits to the most needy and failing ?

Your point that there is "the response to need - not just the relief of poverty" is one well made. A pension that held its value would obviate the top ups, allowances and disregards etc that today proliferate.

I wonder if the average pensioner sees their pension as an 'income flow', subject to smoothing, or their life and income entwined with social contingencies, transference arrangements or unexpected

liabilities. I would imagine that they think of it as a replacement income, a wage for 40 years of contributions and simply budget as they had done before retirement.

David Laraman (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 05/01/2010 - 12:43

Further to my earlier point which you have acknowledged, it would be more accurate if line 1 were amended to read "..per household.." rather than "..per person..".

Mr Timothy Caves (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 11/01/2010 - 13:26

A serious element in fuel poverty is in the rented housing sector where landlords estimate a heating charge which is stated on the rent card. if the tenant gets behind with the payment they are threatened with eviction or can have money deducted from their benefit payments until any arrears are repaid. Since 2003 it has been illegal for any landlord to profit from the resale of electricty or gas (OFGEM decision under the public utilities act 2000). However OFGEM left it up to the tenant to bring a case against their landlord in the cpunty court. In 2002 OFGEM stated that 800,000 tenants where being illegally charged (the landlord was breaching the "maximum resale price" MRP directive). Ofgem could not give me a update estimate of the present situation. I estimate that it may now be 2,000,000 tenants. Since 2003 there is no record of any tenant being able to bring an action in the courts. I hope to bring a test case against my council landlord in Southampton on behalf of myself and many other tenants who are subject to unfair estimates of heating charges, (this occurs because their is not a robust methodology for calculating heating charges and a city wide estimate is used because the council call the heating "communal", this has led to the stupid situation that many tenants in bedsit accomadation are annually paying 3 times as much as some tenants in three bed flats!). I will not be entitled to legal aid and the council will use considerable legal resources at its disposal to fight my claim, it will be a David and Goliath legal battle.

On a positive note myself and a small delegation of council tenants met with John Denham MP the minister for Communities and Local Government. He has agreed to give serious considerstion to enabling section 108 of the 1985 Housing Act. This would give tenants the right to know how their heating charge has been calculated. At the moment a council can refuse to even explain to the tenant the basis for a charge, and the tenant has to use the FReedom of Information Act to obtain this information!

I hardly need to remind other contributers to this site that although 60% of affordable housing tenants receive housing benefit the heating charge has to be paid from disposable income (pension, incapacity or unemployment benefit).

Robert Whiston (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 27/02/2010 - 01:14

Mr Timothy Caves makes some excellent points. One aspect that must be addressed further is the role of the Regulator in the former nationalised industries. In my personal opinion, these persons are toothless and therefore ineffective. It follows that they are overpaid for what they do. They are not radical enough to bring about change or protect consumers. Nor are they fleet of foot.

How can a person on minimum income afford to take anyone to court ? When Grade II listed buildings, ie houses, are being butrchered in Islington by untrained workers, and the many layers of agenices involved fail to respond, why should we suppose for one moment that court action wil bring about a change for the overcharged ? The severe weather of Jan and FEB 2010 will, hopefully, expose all the weaknsses of the heating problem for th7KCZe elderly that have been papered over up until now.

Stew Green (not verified) wrote,

Sat, 19/11/2011 - 22:54

- Since the news unsubstantiated news headline "Fuel poverty 'will claim 2700 victims this winter" is all over the media last week.. do you any plans to update this article.

- Is there any other scientific data now , other than "it's obvious" ?