Missing the target or missing the point?

Figures published today by the School Food Trust show that the Government’s target of increasing the take-up of school meals is going to be missed. Is this a failure? Yes and no.

Yes, judged by the blinkered targets ministers set, which simply count the numbers of pupils eating school meals and take no account of the nutritional content of those meals. No, if today’s school meals are nutritionally sounder than those pupils used to be offered. In that case, today’s figures show a gain that ought to be celebrated.

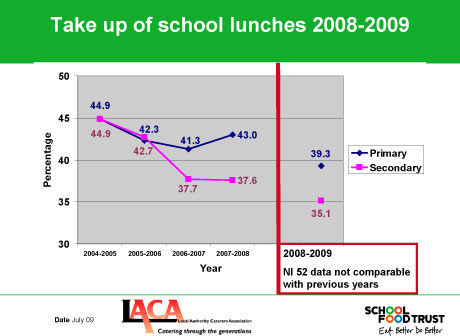

Ministers decided that the target should be to increase the take-up of school meals by 10 per cent in England by this autumn, against a baseline of 2005-06. In that year, according to the School Food Trust, 42.3 per cent of primary school children and 42.7 per cent of secondary pupils ate school lunches.

Today’s figures show the proportions have fallen to 39.3 per cent in primary schools, and 35.1 per cent in secondary schools – though the trust adds that these figures are not comparable with the earlier ones because a different and more complete survey is now being done. (How success or failure against the targets can be measured if the figures are not comparable is not explained.) Here's the chart showing these changes:

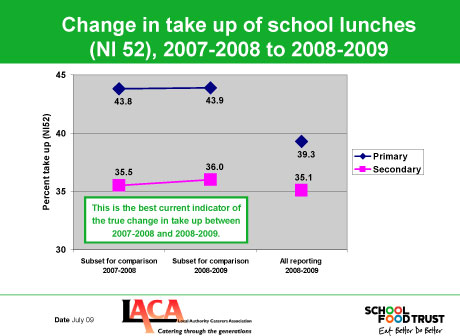

The trust headlines these results as “historic declines in school meals numbers halted” – a bit of an exaggeration, since this graph seems to show the opposite. But by taking a subset of this year's figures from schools that used the new methodology (called NI 52) in both years it has convinced itself that the percentage has increased from 43.8 to 43.9 per cent in primary schools between 2007-08 and 2008-09, and from 35.5 to 36 per cent in secondaries.

Clear so far? The trust's claim that the historic decline has been halted appears to be based on a subset of figures for this year and last which paint a much more favourable picture. With the best will in the world, nobody can make a trend out of such tiny changes in a single year.

But what the trust is trying to do is both to improve the quality of meals, and increase the take-up. Assuming the quality has improved since the pre-Jamie Oliver period, and take-up has remained roughly the same, then something worthwhile has been achieved. If 36 per cent of secondary school pupils are eating well, compared to 42.7 per cent eating badly back in 2005-06, that is a gain.

But if schools ministers don’t count sensibly, by putting value on nutritional content, what hope is there for pupils? Let’s recognise success, and celebrate it, irrespective of naive target-setting.

(Sheila Bird is from the MRC Biostatistics Unit in Cambridge. She chairs the Royal Statistical Society Working Party on Performance Monitoring in the Public Services.)