Predicting the number of civil partnerships

The Prime Minister wants civil partnership ceremonies to be held in the Palace of Westminster, he told a Speaker’s conference this week.

Heterosexual couples with parliamentary links have been able to marry there for years, but Mr Brown wants to extend the privilege to homosexual couples – and perhaps throw open the doors to a much wider range of couples, not just those who are MPs, peers, or their relations. Such a change, he believes, would make Parliament more representative of the nation as a whole.

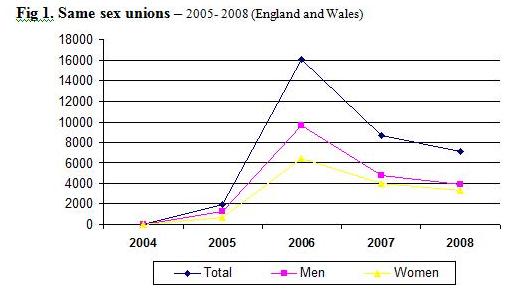

What’s the demand likely to be? Perhaps not quite as many as Gordon Brown imagines. After a surge in 2006 when UK law first recognised same-sex partnerships and 16,000 gay couples tied the knot, numbers have declined significantly. (Fig 1)

In attempting to estimate future trends, I will draw on statistics from the Netherlands and from Scandinavia, where laws allowing same-sex relationships to be registered came into force earlier. They too show a surge at the start, as couples who have long wanted their partnership to be recognised take advantage of changes in the law, followed by a decline.

There is, however, evidence to suggest that in all these countries a more stable era has now been reached. My guess is that after a preponderence of male same-sex unions, civil partnerships in England and Wales will settle down at a level of about 4,000 a year for men and 2,000 a year for women.

The first country to introduce legal recognition of same-sex unions was Denmark in 1989, and the term “registered partnership” was invented for the purpose. Today many European countries have similar legislation, providing same-sex partnerships that in practice hardly deviate from the concept of marriage.

Norway introduced this in 1993, Sweden in 1995, Iceland in 1996, the Netherlands in 1998 and Finland in 2002. By 2003, same-sex unions had been given legal recognition in one form or another in Germany, France, Hungary, Portugal and Belgium.

The Netherlands, which had registered same-sex partnerships since 1998, amended its marriage Act in 2001 to grant same-sex couples a marriage status equal to that of opposite-sex couples. So the Dutch experience can give us some idea of how trends in same-sex unions may go in the UK. In March 2006, Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek) released estimates on the number of same-sex marriages since inception. The pattern of a surge and tail-off is very similar to that seen in seen in England. (Fig 2).

Further data from Statistics Netherlands (Fig 3) trace the trends both for partnerships and for marriages. The effect of the marriage legislation in 2001 is to reduce the number of registered partnerships , but not to eliminate them altogether. In Holland, some same-sex couples choose to marry, others to register a partnership. By June 2004, cumulatively more than 6,000 same-sex marriages had been performed in the Netherlands.

A very similar pattern holds in Norway and Sweden (Fig 4). Once again a collapse in numbers is seen after the initial euphoria but the level of partnerships recovers after about five years and hits a plateau. More recent data from Sweden show a strongish recovery in numbers after 2002, back to the levels seen in 1995.

Interestingly, women have now overtaken men in the total number of registered partnerships in Sweden, but the number of partnerships remains low: about 250 a year for women and 150 a year for men in 2008, and a cumulative total of 1,223 female and 1,214 male partnerships (Fig 5). In the same year, there were over 50,000 heterosexual marriages in Sweden , where marriage as conventionally understood has recovered to levels not seen for 30 years.

The very latest Swedish data covers the month of May 2009, when legislation first permitted marriage, as opposed to partnerships. In that month, 48 same-sex couples married, but women heavily outnumbered men: 37 female couples, and only 11 male.

When the legislation was introduced in England and Wales, some critics said that it would diminish the status of marriage and make it less likely that heterosexual couples would marry. The Swedish data seem to contradict this.

On the basis of experience abroad, I have attempted to predict a possible trend for same-sex marriage in the UK. I believe that it will stabilise at a figure representing the small minority that homosexuals represent in society and the minority of those homosexual who wish to commit to one another. (Fig 6).