False choice over where to give birth

More than 90 per cent of women are denied choice in where they give birth, charges the National Childbirth Trust in a new report.

But the Department of Health insists that 81 per cent of women are offered choice, citing a 2008 report by the Healthcare Commission. Dr Sheila Shribman, National Clinical Director for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, accuses the NCT of flawed methodology and out of date data.

Who’s right? It depends on how you define choice, and how you measure it.

In April 2007, ministers promised that by the end of 2009 women in England would be able to select where to give birth: at home, in a midwife-led birth centre, or in a hospital. Given the constraints on the service, this was a rash promise. But is it going to be missed by as big a margin as the NCT claims?

To meet this guarantee, says the NCT, women must not only be offered all three alternatives but local NHS services must also be in a position to provide whichever is chosen. To determine whether the second condition is met, it sets an arbitrary figure of 5 per cent as a proxy measure of “reasonable access to a home birth” and makes reasonable (but equally arbitrary) judgements about how far a women can be expected to travel to a birth unit – 7.5 miles in town and 15 miles in the country.

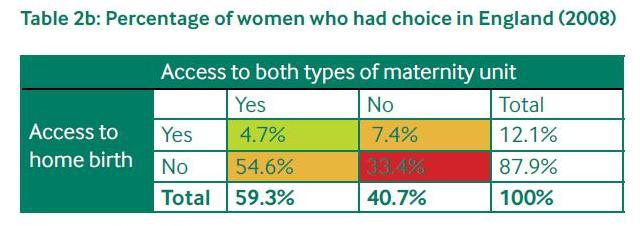

The table below summarises its findings for England. (The UK as a whole shows a similar pattern, but the devolved governments have been more prudent in what they have promised, so the argument focuses on England where the choice guarantee has been explicitly pledged.)

The table shows that only 4.7 per cent of women have access to home births and to both types of maternity unit – hospital-based or midwife-led. This is the figure that led to the claim that more than 90 per cent of women are denied choice. Actually it is 95.3 per cent.

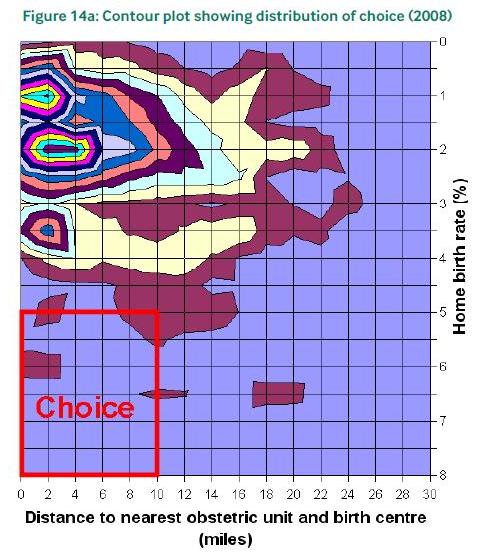

How sensitive is this to NCT’s definitions? Helpfully, the authors provide a contour plot, (their figure 14a, below) which allocates women to a place on the grid according to the home birth rate in the areas where they live and the distance to a birth centre or an obstetric unit. Those offered the full range of choice occupy the box at the lower left.

The plot shows that an increase in home birth rates from 2 per cent to about 6.5 per cent would shift a large part of the distribution into the choice box. Alternatively, if you deemed a 2 per cent home birth rate acceptable, the box would itself shift upwards to include most of the distribution. If you further increased the acceptable distance from an obstetric unit or a birth centre from 10 miles to 20 miles, the box would expand to incorporate a large proportion of all births.

So how many women have full choice depends on precisely how you define the parameters.

The NCT did not ask women if they had been offered any choice. The Healthcare Commission did. Reporting in 2008 on a survey of 3,000 recent mothers, it said that, overall, 80 per cent of women reported that they had been given this choice at the start of pregnancy and 58 per cent were offered a home birth. This is the basis of Dr Shribman’s claims.

But how realistic was that offer? The HCC found that about two-thirds of trusts (65 per cent) had only hospital obstetric units, and thus could not offer the full range of choice as defined by both the DH and the NCT. Add to that the shortage of midwives to attend home births and it begins to look as if the Government's promises are empty.

Home births are increasing, but are still well short of 5 per cent. The average in England is 2.8 per cent, up from 2.1 per cent in 2001; in the UK as a whole, there were 20,547 home births in 2007, an increase of 62.8 per cent compared to 2001, against an increase in total births over the same period of 15.3 per cent. So there is a long way to go. For comparison, around a third of the births in the Netherlands take place at home.

The NCT report is a thorough piece of work. It takes the Government at its word, and shows that it is not providing the full range of choice it promised. The puzzle is why ministers promised something that could not plausibly be achieved.

Samuel (not verified) wrote,

Tue, 24/08/2010 - 11:20

Percentage of women who had choice in England(2008)

Great info.I don't know the exact percentage but pleased to see such a great info.Chicago movers