Where’s best to give birth? Easy question, tough to answer

Note: the authors of the Birthplace Study have taken serious issue with this analysis, and I have posted their comments at the end. For ease of reference I have annotated in bold the claims they rebut and listed the rebuttals by number in the comment, which is by Dr Jennifer Hollowell, Prof Peter Brocklehurst, Elizabeth Schroeder and Prof Stavros Petrou on behalf of the Birthplace co-investigators.

The Birthplace Study, published in November last year, was intended to answer long-standing questions about the safest place for women to give birth in the UK – at home, in obstetric units in hospital, in freestanding midwifery units, or in midwifery units located on the same site as an obstetric unit (ie, in hospital).

There is little secret that the Government, which has offered women choice of the place of birth, would prefer them to choose cheaper options – midwifery units rather than hospitals – and the results have been presented by some as justifying this preference. (1)

A paper published in the current issue of BMJ shows what the cost difference amounts to (the full online version, published a couple of weeks ago, is here, or in a longer form, as Report 5 on the Birthplace Study website). A team led by Elizabeth Schroeder of the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit at Oxford reports that births at home are cheapest - £565 cheaper than birth in an obstetric unit for all women at low risk of complications. The corresponding figure for freestanding maternity units is £196, and for maternity units in hospitals is £170.

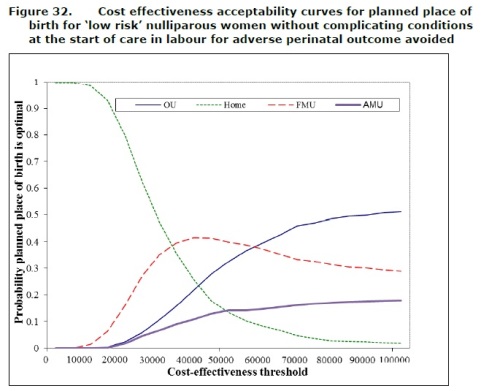

These are quite small differences - smaller still when you look at women having their first babies. And while costs are less, adverse outcomes are more common in home births and births in maternity units of either sort for first-time mothers. (2) This leaves some uncertainty over which is truly the best option. For example, there is a 0.63 per cent probability of home birth and a 0.35 probability of a free-standing maternity unit being the most cost-effective option for low-risk women having their first babies if one sets the cost of an adverse event at £20,000.

The flaw with this study is its short timeframe. The data was limited to adverse outcomes at the time of birth, with no long-term follow-up. Accidents during birth are one of the costliest misadventures it is possible to imagine, so much so that private insurers will not insure against it. A child suffering from cerebral palsy can be disabled for life, with costs running into tens of millions of pounds. Yet the study looks only at immediate costs, which it acknowledges as a limitation.

I’d go further and suggest that it invalidates the whole comparison. A clue is provided in Figure 32 (below), which plots cost effectiveness curves for various thresholds for women having their first baby without complicating conditions at start of labour. At cost thresholds of £60,000 and over, obstetric units (hospitals) have the greatest probability of being the right place for such women to give birth.

So the “right” place is determined by the cost attributed to adverse events and this study cannot calculate what that is. Cost-effectiveness calculations are unhelpful if you leave out what is likely to be the biggest cost. The Birthplace Study couldn’t measure this, of course. But by publishing this paper it may give some people the impression that the answer is clear when it isn’t. (3)

The National Institute for health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is drawing up new guidance on maternity care. Professor Mark Baker, head of clinical practice for NICE, told The Daily Telegraph on Saturday that the guidelines would be based on the best available evidence. The Birthplace Study, which cost £12 million, will certainly be included.

But it is not without its critics, of which the Birth Trauma Association has been the most persistent. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists also raised some issues, suggesting that first-time mothers should be advised of the benefits of obstetric units and midwifery units based in hospitals. For mothers having subsequent children, the place of birth did not appear to affect the outcome.

The BTA has a number of criticisms. They include loss of data, particularly from the freestanding maternity units. With adverse events being so infrequent, it was essential to capture all the data, but the team did not manage to do so. In the case of the freestanding maternity units, where only two thirds returned more than 85 per cent of the data properly, the “lost” data is likely to refer to women transferred from FMU’s to obstetric units because of complications. If so, the data loss flatters the FMUs and makes the obstetric units results appear worse. Failing to record this data cannot be blamed on overwork, since most FMUs have a relatively low throughput. (4)

Nor is it clear that the team was comparing like with like. Those who gave birth in obstetric units had more complicating conditions at the start of labour, and more of them had other health conditions, too. Nearly 20 per cent had serious problems at the start of labour, far more than in the midwifery units. So the comparison drawn – “no difference in outcomes between midwifery units and obstetric units” – is not a fair one. (5)

If you exclude women with complicating conditions at the start of labour (Table 59, in Report 4 on the Birthplace Study website) the units which returned their data properly did show a statistically significant difference. Adverse events are more than twice as common in FMUs (odds ratio 2.29, 95 per cent CI 1.17 to 4.47) as in obstetric units for women having their first baby. (6)

What of women transferred from freestanding maternity units to obstetric units, either before or after labour? If things go wrong, a transfer to hospital is needed, which may be lengthy if the maternity unit is not inside a hospital already. Such transfers are very common in women having their first baby: 45 per cent of planned home births were transferred during labour or immediately after birth, and 36 per cent of those in freestanding maternity units. The cost-effectiveness study shows that transfers from home took on average 29 minutes, from freestanding units 35 minutes, and from in-hospital maternity units 10 minutes.

Table 31 shows strikingly poor results for women who made this transfer either from home or freestanding units after labour, with more than eight times as many suffering adverse events as those who transferred from maternity units within hospitals. The report does not comment on this in its conclusions. (7)

Among the points made by the RCOG is why, in this low-risk population of mothers, 20 of the 32 deaths were in the home or freestanding maternity unit group (Table 48). The BTA also finds it surprising that no deaths among mothers are recorded at all. Such deaths, though rare, occur at a rate of around one per 12,000, so it is indeed surprising – though not impossible - that in 80,000 births none were recorded. However, these were low-risk pregnancies. (8)

The rapid responses to both studies in the BMJ are worth reading. Generally, midwives are supportive, doctors sceptical, and campaigners for safe childbirth such as the BTA and Pauline Hull, a pro-Caesarean campaigner and author, critical. NICE should beware of placing too much weight on the Birthplace Study.

Chris Hughes (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 02/05/2012 - 05:35

As a member of a health authority in the 1980s when we had to look at the safety issues around the whole range of options for changing maternity services including the appropriateness of a hospital unit without dedicated paediatric and anaesthetic cover, I formulated a proposition:-

Midwives support all technology over which they have control and oppose all technology over which they do not.

The proposition is generalisable more widely

The Birthplace co-investigators (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 10/05/2012 - 07:58

1.We are unaware that this is the government agenda with relation to planned place of birth. No policy document makes this statement and the DH comment on the release of the results of Birthplace simply confirmed the government’s commitment to women having choice about their planned place of birth.

2.This statement is incorrect. Although we found an increase in adverse perinatal outcomes for first time mothers planning birth at home, we did not find an increased risk for first time mothers planning birth in either sort of midwifery unit – see below

3.Cost and cost effectiveness analysis

Both the BMJ article and the full SDO report describe our methods in full and explicitly state that the short time horizon of the analysis is a limitation. In particular, our reports explain that we included only the NHS costs of the intrapartum care episode (including high dependency or neonatal care required by the mother or baby immediately following the birth), but did not include longer-term costs and outcomes, for example the life-long costs caring for babies who suffer serious birth injuries.

These long term data are not available for the full range of adverse outcomes that we measured. Although we know about the costs associated with cerebral palsy, these costs are not available for all of the consequences of the outcomes that we measured. In addition, the numbers of babies born with neonatal encephalopathy is relatively small with no statistically significant differences between the different groups, and only a small proportion of these babies will develop cerebral palsy.

Also, other outcomes, such as caesarean section, were much more frequent that encephalopathy (over 40 times more frequent overall) and these can have major long term implications for subsequent pregnancies (including uterine rupture with neonatal encephalopathy and cerebral palsy). Once again, these long term risks are just beginning to be quantified and we have no information about the costs associated with these later events. So to take only one possible outcome and compare the long term costs between groups would not have been helpful.

The criticism that our focus on short term economic outcomes invalidates the study is not true. The study is valid but is limited, a weakness that we acknowledge. It is the interpretation of these data and how they are implemented that may be called into question. But this does not mean we agree with the implication that this paper should not have been published:

• This study, for the first time, provides a detailed, individual patient level analysis of the intrapartum care costs to the NHS of planned births in obstetric units, alongside midwifery units, freestanding midwifery units and at home. The study provides the most reliable short-term cost and outcome data available to date and these findings can now be used by us and/or other researchers to develop longer-term cost-effectiveness models. As such it is entirely appropriate to publish our detailed methods and results in a peer reviewed journal. Details of costs and this cost effectiveness analysis have already been passed on to the lead health economists involved in updating the NICE intrapartum care guideline and we understand that these are being used to develop a longer term cost effectiveness model to inform the updated guideline.

We also consider that the results, despite their limitations are of use to decision makers in their current form:

• The Birthplace cohort study did not find evidence of any significant differences in perinatal outcome by planned place of birth for multiparous women so we would argue that the cost-effectiveness analyses relating to multiparous women are not misleading despite the limitations noted above.

• We consider that there is value in documenting the short term costs of intrapartum care. For example, the findings highlight the fact that the higher intervention rates in obstetric units contribute to the higher overall costs of OU births and, for multiparous women, these higher costs are not associated with better outcomes for the mother or baby.

One final point to bear in mind is that many managers in maternity care thought that the costs of planned birth at home would be substantially higher than in hospital because the higher intensity of midwifery care (almost always 1 to 1 care) would result in higher costs overall. However, our analysis has shown that the substantial decrease in interventions in labour has off-set this increase in midwifery staffing, so resulting in a modest cost-saving for births planned at home.

4. Completeness and quality of data

We cannot rule out the possibility that non-response may have led to the under-reporting of important outcome events and could have biased our findings, but for the reasons explained below we believe that the magnitude of any non-response bias is likely to be such that it would not affect our overall conclusions regarding the safety of different planned birth settings: The relatively high transfer rates in the non-obstetric unit settings suggests that the way we collected data when women transferred to another location did work. Also, although we report on the proportion of units achieving an 85% response rate, the response rates achieved in the majority of sites was, in fact, substantially higher.

• The response rate achieved in the 35 FMUs (66% of all included FMUs) that met the target response rate of 85% or more was actually 97%, ie those units included 97% of eligible births. This makes us fairly confident that any non-response bias would have had a very small effect on the adverse perinatal outcome event rate estimated in this subset of units. A sensitivity analysis (discussed further below) found that the adverse perinatal outcome event rate in nulliparous women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour was 5.2 events per 1000 births in the 35 FMUs with a high response rate, compared with 4.5 events per 1000 births in the equivalent main analysis.

This relatively small difference (~15%) suggests that the effect of non-response on outcomes in planned FMU births is likely to be small, and would not have affected our overall conclusion that perinatal outcomes were not significantly different in planned FMU births compared with planned OU births. Indeed, we have estimated that we would have had to miss 7 adverse perinatal events in the FMU group (equivalent to a crude event rate of approximately 6.1 events per 1000 births) for the unadjusted FMU event rate for nulliparous women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour to differ significantly from that observed in the obstetric unit group in the main analysis (table 25, SDO report).

5. Comparing like-with like

It is incorrect to say that we did not compare like with like. The finding that women without any known medical or obstetric risk factors in the planned obstetric unit group had a higher prevalence of complicating conditions such as prolonged rupture of membranes and meconium staining was unexpected and led to additional analyses being conducted to ensure that the comparisons made were fair and valid. In the BMJ article (Table 3) and the full SDO report (Table 23 and 25) we report adverse perinatal outcomes both for the full sample of low risk women and for the restricted sample of low risk women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour. Interestingly, the conclusions drawn from the two sets of analyses do not differ:

• For nulliparous women, the odds of the primary outcome are higher for planned home births but not for either midwifery unit setting.

• For multiparous women there are no significant differences in the incidence of the primary outcome by planned place of birth.

• Interventions during labour are substantially lower in all non-obstetric unit settings.

6. Misinterpretation of table 59

It is worth stating that a detailed pre-specified analysis plan was produced for the cohort study to ensure that we were not misled by spurious associations when undertaking the analysis, and that this plan set out what comparisons would be made, what outcomes would be included (as well as how composite outcomes would be constructed) - and that this was reviewed and signed off by our Independent Advisory Group. This was to ensure that there could be no accusations of data-dredging.

Table 59 in appendix 6 of the SDO report related to the findings of one of several sensitivity analyses conducted and it is wholly misleading to present these results as if they represented the findings of the study. The results of the main analyses (table 25) show that for nulliparous women without complicating conditions at the start of care in labour, adverse perinatal outcomes were not significantly more common in planned FMU births compared with planned obstetric unit births (adjusted odds ratio 1.4, 95% CI 0.74 – 2.65).

It may be helpful to explain the purpose of the additional sensitivity analyses reported in tables 57 to 59 of the SDO report (appendix 6) and to explain how these were interpreted by the Birthplace investigators:

• In many large studies, a range of additional analyses are undertaken to make sure the results are reliable. A decision to change the conclusions based on these additional analyses is made only if the additional analyses produce convincing evidence that the main results are wrong. This was not the case with Birthplace for the following reasons. First, these additional analyses (appendix 6) involve doing lots more statistical tests so they can throw up spurious associations by chance, so it’s important to be cautious about interpreting these findings without taking account of this fact.

Second, the results have to be believable. For example, in the analysis shown in table 59, the outcomes for first time mothers in the hospital obstetric unit appear to be better than the outcomes for women having a second or subsequent baby in the hospital obstetric units. This is contrary to what is known about risks for first babies and clearly illustrates the type of spurious result that sensitivity analyses can throw up.

• These are the reasons for not using this result to change the overall findings reported in the main BMJ article. The sensitivity analyses were all fully reported in supplementary material published with the BMJ article so the journal’s peer reviewers would have been aware of these results and clearly considered that these did not undermine the findings reported in the main article.

7. Are transfers ‘riskier’ in planned home and FMY births?

Table 31 compared the outcomes for the babies of women who did and did not transfer from each of the non-obstetric unit settings, by timing of transfer (before or after delivery). The table does indeed show markedly higher rates of adverse outcomes for the babies of women who transferred from home and FMUs after delivery compared with women in the alongside midwifery unit group who transferred after delivery, but it is incorrect to interpret these results as showing that transfers from home and freestanding midwifery units are riskier for women and their babies as is suggested in the article

The reason for the striking difference relates to the fact that in the alongside midwifery group, women did not need to transfer after delivery if their babies required admission to a neonatal unit, whereas in the other settings (home and freestanding midwifery unit), women transferred with their babies if their babies required admission. This means that all poor baby outcomes requiring hospital admission get included in the ‘transferred group’ for planned home and FMU births, whereas many of the poor baby outcomes in women in the planned AMU group occurred in women who did not need to transfer because their baby could be admitted without them moving. The higher incidence of adverse outcomes observed in women who were not transferred from AMUs (also shown in Table 31) is consistent with this interpretation.

Overall, there is no difference in adverse outcomes between FMUs and AMUs, suggesting that transfers from FMUs do not make planned birth in an FMU riskier than planned birth in an AMU.

8. More deaths in the home and freestanding midwifery unit groups?

It is certainly an interesting observation that there were more deaths in these groups but the numbers are small and this distribution could have arisen purely by chance. We are aware that the RCOG and others may have tested the differences in deaths for ‘statistical significance’ but this kind of post hoc testing is not valid as it has a high risk of generating ‘false positive’ results, i.e. wrongly concluding that a difference or association exists.

No maternal deaths?

A large proportion of maternal deaths occur in women who have pre-existing medical or obstetric risk factors, who are obese, or who have not received antenatal care. All of these women would not be “low risk” and therefore included in this cohort study. We do not consider it surprising that no maternal deaths were recorded in this cohort of low risk women.