Happy Hour in the A&E

Targets are usually well-meant. They're designed to inject a note of urgency into otherwise sluggish systems and raise productivity. But the outcome is seldom strictly what anybody intended.

Take the four-hour wait in Accident and Emergency Departments, designed to eliminate the horror of lying on a trolley in A&E for a day and a half in the hope that somebody will eventually get around to you. This target is widely considered a "success" - that is, hospitals mostly claim to have met it, and the public hubbub over A&E waits has diminished.

But the NHS never planned that patients' care should be squeezed into a Happy Hour of frenetic activity as the clock ticked away. To avoid breaching the target, patients are all-too-often treated in a rush in the last 20 minutes of the four hours. The target was supposed to set a maximum, not a norm.

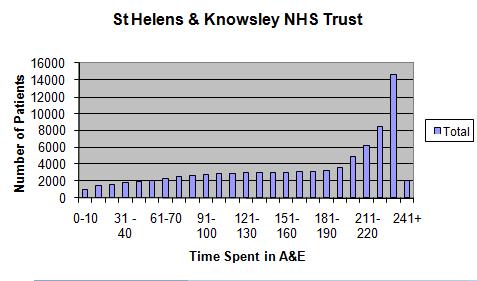

A series of Freedom of Information requests by the Liberal Democrats has shown how often the target is abused in this way. It includes some striking distribution curves for the hospitals that responded - many didn't, to their shame - showing a sudden peak in activity as the four-hour deadline approaches.

Take St Helens & Knowsley NHS Trust (above). Here it looks as if the clock is ticking peacefully away, as patients wait and doctors and nurses go about their business, until suddenly all is action. In fact, say the LibDems, 26.6 per cent of all patients passing through the A&E at this hospital are treated in the last 20 minutes, and more than 15 per cent in the last ten.

Is this good medicine? The LibDems don't think so, and they have a point. Not all hospitals have as unbalanced a picture as this, but many are nearly as bad. Of the trusts that responded to the FoI requests, 16 had higher "spikes" of activity than did Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust, where neglect of what was happening in A&E led to poor care.

The Healthcare Commission report into Mid-Staffs found that doctors were put under a lot of pressure not to breach the four-hour target, and were diverted from dealing with the seriously-ill to those with minor problems who had been waiting longer and who would breach the target unless admitted or discharged in short order. Nurses told the commission that their jobs had been threatened if they allowed the target to be breached.

The LibDems got responses from 95 hospitals, while 16 chose to answer a different question, 41 failed to respond and three claimed exemption under the act. One had the brazen nerve to claim that it did not collect data on the time spent in A&E. Given the Government's obsession with targets, this excuse doesn't wash.

What's to be done? Operating without a target, on past experience, would be worse. Perhaps a more sophisticated target would work better, or perhaps it would simply inspire more sophisticated gaming. It's just possible - as some doctors claim - that the peaks in activity actually represent good medicine, as it can make sense to keep a patient under obervation in A&E for a few hours.

But the LibDems are almost certainly right to argue that this target is distorting care. They have referred the figures to the Health Secretary and to Cynthia Bower, chief executive of the Care Quality Commission (successor to the Healthcare Commission). We'll see if anybody responds.

But don't hold your breath. A study by Thomas Locker and Suzanne Mason of Sheffield University, published in the BMJ in 2005, found a very similar pattern. Ambulance response times showed similar anomalous peaks, they reported, adding: "Such performance targets should be monitored in such a way that any improvement can be shown to represent meaningful improvement of the patient's experience of the healthcare system."

Did anything happen? Not so far as I can tell.