Sats tests give a false impression of educational progress

One in ten white boys is leaving school with fewer than five GCSEs, the benchmark for basic secondary school education, according to figures released by the Department for Children, Schools and Families in response to a Freedom of Information request.

In some cities, the rate is much higher – 22.3 per cent in Manchester, 22.2 per cent in Southwark, south London, 20.5 per cent in Hull. Professor Alan Smithers of Buckingham University commented in the Daily Mail that five GCSEs was not hard to achieve after 11 years of education. “If they can’t it says something very important about how our education system is failing their needs.”

Last week Michael Gove, the Shadow Schools Secretary, blamed a culture of “defeatism and political correctness” for poor school results, prompting a response in today’s Guardian by 26 leading heads from the state sector. They claim that recent years have seen a strong focus on raising the quality of teaching and learning, and “increasing the number of young people who achieve well.”

There may well have been such a focus, but measuring its impact is difficult. The puzzle is that according to exam marks, things are getting better and better.

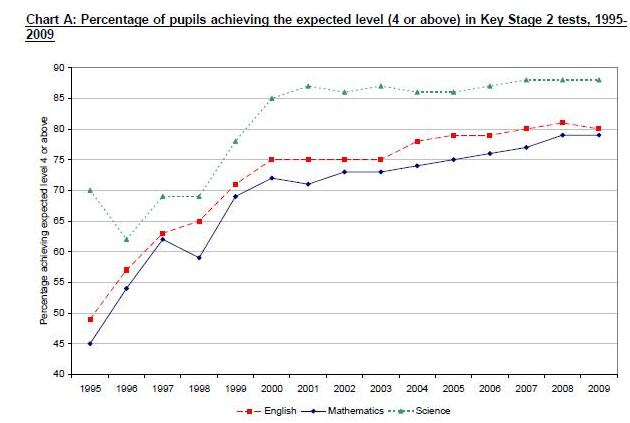

For example, rising marks in SATs grades for children aged 11 (see graph) paint a rosy picture of rising standards. When this year’s results were published on 4 August, a lot of attention was focussed on a small decline in the attainments in English, prompting Schools Minister Diana Johnson to say she was 'concerned' by the apparent lack of progress.

Yet this apparent stalling in Sats grades for children aged 11 should not be the source of concern. It is small – just 1 per cent – from a record level of 81 per cent the previous year. The maths and science levels were actually on a par with last year, at 79 per cent and 88 per cent respectively.

True, this is the first time that the English results have fallen since the exams begun in 1995. But this follows a rapid rise, with those reaching expected standards in English rising from 49 per cent in 1995 to 80 per cent now. This huge rise was bound to plateau sooner or later, with a proportion of children unable to obtain the expected level no matter how strong the help. There will be the odd year where there are slight blips.

To worry over a single percentage point decline is to miss the point, which is that Sats results are almost wholly meaningless. They fail to work as a consistent measure of standards over time. Much of the initial stunning rise was caused by teachers quickly learning how to teach to the test, rather than actually teaching any better. The current halt in progress is because teaching to the test has now become the status quo.

Another problem is that each year a different paper must be set (to avoid cheating), which will inevitably vary in difficulty from previous years. Thus, a new boundary must be set each year, and it is very easy for this to be set a mark too low, causing a rise in grades unreflective of any change in general ability.

Research by Professor Peter Tymms in 2004 estimated that the real progress in literacy standards was only about one-third of the reported rise (58 per cent rather than 75 per cent). So why does Ms Johnson incessantly remind everyone of the “17 percentage point increase since 1997” and the “98,000 more pupils now gaining this level [level 5 in maths] than in 1997.” The rise was illusory, proven to be so, and should now be forgotten.

Both the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) and the National Union of Teachers (NUT) have threatened to boycott next years Sats; the former went as far as to call them “meaningless nonsense” and complained that teachers are obliged to “teach to the test”. A review led by Professor Robin Alexander of Cambridge University, to be published on October 19, is expected to say that the Sats-driven focus on English and maths has been damaging. The Government's own review, published earlier this year by Sir Jim Rose, excluded consideration of testing.

An independent system rather than our statutory test data would be a more accurate method of monitoring standards over time, as is found in several other countries. Whilst we continue to test our children with Sats we will never be able to gain a clear insight into the real change in standards of education within our primary schools.