Taking liberties with the “liberal gene”

Scientists find the gene that makes you a liberal, reported the Guardian, the Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph, and the Daily Express last week.

Right? Wrong. The authors of the study specifically disavow this interpretation of their work, published in the Journal of Politics.

Let me quote them: “It is important to note that the 7R allele (the genetic variant they studied) by itself does not make a person liberal ... the 7R allele is not directly associated with ideology.” What the study showed, and they explained very clearly, is that the 7R allele of the D4 dopamine receptor gene (D4RD ) is linked to liberal beliefs in those who have a lot of friends, but not in those who do not have a lot of friends.

There is no statistically significant link between 7R and political ideology (p = 0.35) or between 7R and the number of friendships (p = 0.87). So the gene does not determine how many friends you have, or how you vote. The gene is linked, rather, to the interaction between numbers of friends and political leanings.

The authors, led by James Fowler of the University of California at San Diego, put their conclusion this way: “Among those with 7R, we find that the number of friendships a person has in adolescence is significantly associated with liberal political ideology.”

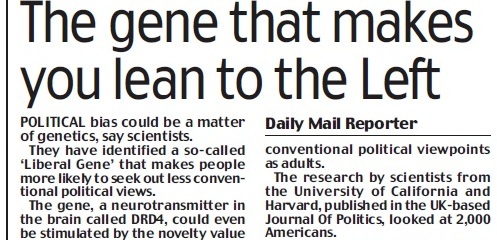

How the Daily Mail headlined the story

But that's a rather different story, both harder to tell and possibly also harder to credit. It’s evident where the headlines came from, however. Science writers derive much of their raw material from a site called Eurekalert, run by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, where embargoed press releases are made available to those with passwords.

The press release for this story (now generally accessible since the deadline has passed) is headlined “Researchers find a ‘liberal gene’”. It is more carefully written than most of the stories derived from it, and quotes Dr Fowler as saying: “It is the crucial interaction of two factors – the genetic predisposition and the environmental condition of having many friends in adolescence – that is associated with being more liberal”. This quote appears in most media reports, but is a bit too subtle for the intro or the headline.

The explanation of how this interaction might work is pure arm-waving. The 7R allele has been linked in the past to novelty-seeking behaviour. Some people (in this sample, 62 per cent) have no 7R allele; some have one copy (33 per cent) and some two (5 per cent).

The authors suggest (in the press release) that those who possess one or two copies, and who have a greater-than-average number of friends, would be exposed to a greater variety of social norms and lifestyles, which might make them more liberal than average.

Maybe, but this may not sound terribly persuasive to everybody. What other possibilities are there? One is that the team has simply examined so many possible interactions that one proved statistically significant at the p = 0.05 level. The authors discuss this, pointing out that if one were comparing 100 genes and 100 environmental factors, there would be 10,000 possible interactions, many of which would appear to be significant. In this case, eight alleles were compared, greatly reducing the number of possible interactions but not ruling out a false positive.

They also point out that the strength of the association is quite small. Carriers of 7R who have ten friends rather than none are shifted leftwards by 40 per cent of a category on a five-category scale, ranging from very conservative through conservative, middle-of-the-road, liberal to very liberal.

That means a person with two copies of the allele and 10 friends could be moved almost half the way between conservative and middle-of-the-road, or between middle-of-the-road and liberal, compared against a person with two copies of the allele and no friends.

But since only 5 per cent of the sample, or 100 people, carried two 7R alleles, the base upon which this conclusion is founded is narrow. Replication is needed in other populations and age groups, the authors say.

It’s fair to conclude that none of the press reports captured the complexity of this story. Gene-environment interactions tend always to be reported as if they were gene-only, which in trying to explain human behaviour is clearly over-simplistic. We need a better way of explaining what the authors of this paper were actually claiming.