Youth unemployment: bad or very bad?

How bad is the plight of the country’s youth? The rise in youth unemployment revealed by the ONS last month produced some dramatic quotes.

Ed Miliband, leader of the opposition, joined a host of others in raising the spectre of the “lost generation”. Brendan Barber, TUC general secretary called them “grim jobless figures" and said: “With more than a fifth of young people out of work, we face a real danger of losing another generation of young people to unemployment and wasted ambition.”

The latest to add his voice is Jonathan Portes, the new director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, in today's Times. He called for "immediate and urgent" action to tackle the problem,

On the headline measure promoted by the ONS, there was (nearly) a “record” high rate of youth unemployment – the latest month’s rate of just over 18 per cent almost matched that seen for a month just over a year ago and was above the 17.8 per cent seen back in 1993.

It looks bad. And it might get worse tomorrow when updated data come out. But here are three other perspectives on the data.

1. Look at the numbers.

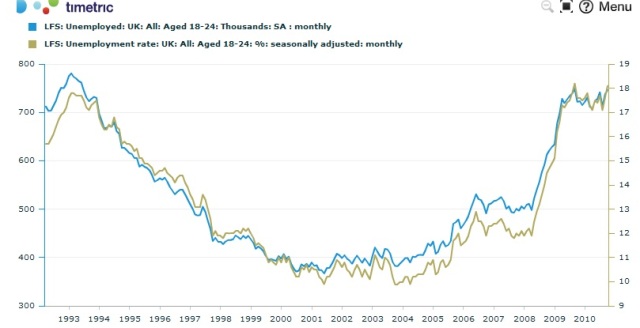

Nearly 800,000 18-24s were unemployed in the early 1990s, compared to around the 700-750,000 mark of recent months. So, in terms of actual numbers, as opposed to rates, on the same measure over the same period, the situation is not quite so bad now as it was. Chart 1 (below) shows this – the rate is at a high and the number line is not.

The ONS definition of youth unemployment rates is, to say the least, a bit odd. The rate the ONS publishes is not the proportion of youths who are unemployed. Instead, it gives us the youth unemployment as a percentage of the economically active (the employed and unemployed), excluding the so-called inactive. This is a vital if subtle difference as the proportion of inactive youths has been rising sharply for more than a decade, as tertiary education expanded. In other words, the denominator used to calculate the rate has been shrinking.

This means that, if the number of youths stays the same and the number unemployed stays the same, the rate of youth unemployment will rise if more youths leave the labour market by going into education! The economy is no worse – indeed more education bodes well for the future – but the rate of youth unemployment has risen.

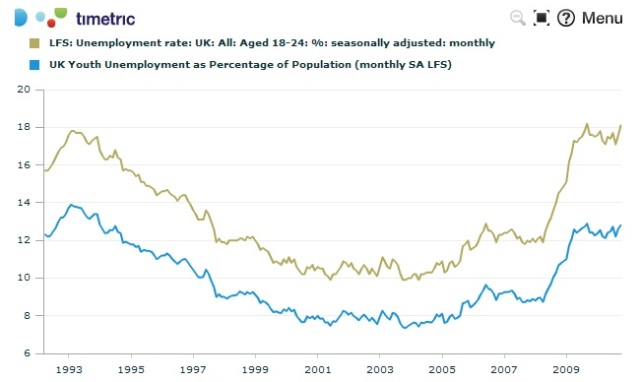

Chart 2 shows the unemployed youths as a proportion of all youths alongside the official rate. The former is at a much lower rate – less headline grabbing – and has risen far less steeply. An unemployment rate of sub-13 per cent and over a percentage point below where it was at the last peak is just not so sexy – despite it being a more accurate measure of youth unemployment. The widening gap between the two lines reflects the increase in youngsters going to university. (By the way, the ONS does not publish the figures we put in the chart. And the notes on the press release do not explain this oddity arising from the rate they choose to publish.)

The distortion-by-denominator issue is even more extreme when looking at the unemployment ‘rate’ for 16-17 year olds. The ONS published rate is 36 per cent as roughly 200,000 are unemployed and 350,000 are in work. But nearly a million are in education and when they are added to the denominator, the rate more than halves to around 15 per cent. Around 15 per cent of 16-17 year olds are unemployed, not 36 per cent as the ONS publishes.

3 The highest rate since ………

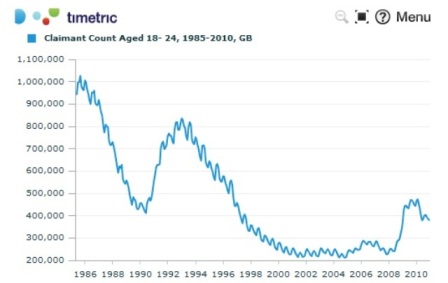

All the figures quoted above come from the Labour Force Survey. This data is by far the best measure of what is going on in the labour market but it has existed for a relatively short time, less than two decades. Prior to that point all we have is the numbers on unemployment benefits. This is less than perfect but, for what they are worth, it is another set of figures that pours cold water on the current youth being the “lost generation”.

The current level of 18-24 unemployment – around 400,000 – is nowhere near the 1 million level seen in the mid 1980s. If there was ever a generation that was going to be lost to high unemployment it was mine! The very same generation that the young are now envious of. (Again this is ONS data but not figures that are readily available in print or on line.)

Yes, the young have got it bad but it is not as bad as many might think reading the headlines.

To summarise: around 3.4 million 18-24s are in work, 1.7 million are inactive (mostly in education, but not looking for work), and “just” 0.7 million are unemployed. These unemployed youths are important and deserve attention but are barely 1 per cent of the population. They are not the only people affected by the slowdown – the millions who are too sick to work and who are ‘inactive’ involuntarily deserve to be given due attention too.

Simon Bricoe is Vice-President, Product, at Timetric

Jonathan Portes (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 21/02/2011 - 13:31

Simon

You are quite correct that comparing rates when there is a time trend in the denominator (driven, as you say, by higher participation rates in education) can be misleading. Equally, however, I suspect your claimant count chart - which suggests things are not nearly as bad as the early 90s, let alone the early 80s - is so distorted by changes in eligibility rules/takeup over time as to be nearly useless for long-term comparisons.

More broadly, while I agree (of course) that young people are far from the only people affected by the slowdown, I don't think there's any question that they've done considerably worse. Over the last two years the number of people in work aged 25 or over is broadly flat; but there are about 350,000 fewer young people in work. This contrast is quite striking.

I think the point, from a policy perspective, is not that things are anywhere as near as bad as they were in the early 80s for young people; they clearly aren't. It is that there is a strong case for early action to avoid the policy mistakes of the early 80s, which the evidence suggests had considerable negative long term effects (both for individuals and for the economy and society as a whole).

Jonathan Portes