Baby boomers built the economic bubble

The generation born in the wake of World War II is getting the blame for the economic mess we’re in.

First it was David Willetts MP, whose book How the Baby Boomers Took Their Children’s Future blamed those born between 1945 and 1965 for stealing the bulk of national wealth and thinking little about the future.

Now Tim Bond of Barclays Capital has put the argument on a more substantial basis. In Barclays Equity Gilt Study for 2010 he accounts for many of the economic twists and turns of the past 50 years simply through demography, and in particular the influence of the baby boomer generation on savings, investment, and the creation of economic bubbles.

The thesis is so simple and beguiling that it attracted no fewer than three Financial Times columnists in Saturday’s paper: John Authors, Matthew Vincent and David Stevenson. Does nobody check these chaps aren’t all writing about the same thing?

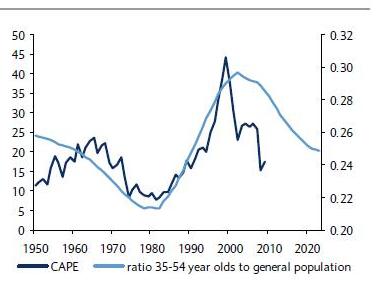

The argument is summarised in the figure below, which plots the cyclically-adjusted PE ratio of US stocks (CAPE) since 1950 against the proportion of 35-54 year-olds in the general population. The match is striking. The rationale is that the 35-54 year olds are the generation most likely to invest in shares: they have the money, can afford to take a little risk, and are not so close to retirement that they need to go into bonds instead.

When there are lots of people in this age group, the capital available to invest is high, and it pushes up PE ratios, the ratio between the price of a stock and its earnings per share. Traditionally, the value of shares has been believed to oscillate around a long term average PE ratio of about 16. When PEs were below this, you could expect share prices to rise, and vice versa.

But the Barclays model is that this equilibrium PE ratio fluctuates, depending upon the proportion of different age groups in the population. Demography rules.

Had we been bright enough to realise this in early 2009, we might have put money into equities as the right moment, Mr Bond argues. Many investors waited, in the belief that the buying opportunity would not come until the FTSE index reached the same depressed levels as in the deep dip of the 1970s.

But there weren’t as many investors in the 1970s, so the equilibrium PE value then was lower. In fact, adjusting for this factor, share prices were as cheap or cheaper in early 2009 as they had been in the 1970's slump. It was a buying opportunity many missed.

In addition to the baby boomers, a second demographic is also important - the numbers of the newly-retired. They tend to be sellers of shares, so when their numbers are rising they exert a downward pressure on share prices. In the period 1996-2002, growth in the numbers retiring slackened at the same time as the equity buyers in the baby boomer generation were increasing. More buyers and fewer sellers produced a “bubble” in share values in the 1990s followed by the crash of 2001-03.

What are the implications for the future if this model is right? The proportion of 35-54 year-olds in developed countries will continue falling, while the proportion of the newly-retired will rise. There are likely to be more sellers than buyers, so equity values are likely to remain low. There could be another decade of poor returns, though maybe not as poor as the past decade. But shares are likely to do better than bonds.

Is it fair to blame the baby boomers, as Mr Willetts does? It’s not their fault that they formed part of a large cohort, as they had no control over that, and their investment behaviour was rational. Few expected when they bought their houses that these would in due course come to represent the bulk of their assets. Most probably believed that their pension fund would be their real banker, but they were wrong.

Baby boomers born in 1945 and facing retirement now on defined contribution pensions will be 70 per cent worse off than those who retired a decade ago, according to an analysis by Life and Pension Moneyfacts. A man contributing £100 a month for 20 years and retiring at 65 with a standard annuity would have earned a pension of £8,998 if he had retired in January 2000, but only £2,542 if he retired in January this year, according to these figures. So it can’t be argued that the baby boomers ate all the pies.

Nick Howell (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 17/02/2010 - 06:16

If that is the sort of analysis that earns Barclays Capital employees their bonuses then the statements that "we need to to pay these amounts to keep key staff" doesn't wash! The world's economic growth plotted on the same graph with the same time lines would not doubt produce the same result. In 1990 you could buy an annuity to give a 10% return and they have been going down ever since. What happened to the benefits of growth thereafter shown indicated by the CAPE figures in the graph?

My mother has been buying and selling shares all her life, she is 84, and has funded her adequate lifestyle on the growth and dividends, not by being a net seller. Nor does she uses a broker, financial adviser, or buy unit trusts as she believes the charges are excessive. As a "baby boomer" myself I am looking for a return on my investments in my personal pension, not towards selling them all and er, doing what with the money Mr Bond?

christopher crossman (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 17/02/2010 - 10:14

So more people with more money chase up prices eh? Brilliant. And how does that justify thousands of greedy bankers (speculating with those same funds at no risk to themselves) paying themselves massive bonuses - in some cases more than the lifetimes earnings of these same baby boomers?

Christopher Crossman

Samantha Richardson (not verified) wrote,

Wed, 08/09/2010 - 07:30

Taking care of my first baby should be careful and have a parenting skills. From this article, I got many tips in taking care of my baby and I've also got alot of ideas in baby care and breastfeedingat www.docsbay.com