More questions on the disabilities “avalanche”

In March the Specialist Schools and Academies Trust (which has now changed its name to The Schools Network) published new recommendations on teaching children with learning disabilities, the result of a two-year research programme paid for by the Department for Education.

I complained then that the research had not been published at the same time as the recommendations deriving from it, an academic discourtesy. But it has now and is available here.Most of the report is about better approaches to teaching learning-disabled children and there’s no reason to doubt the advice is good.

My interest was the narrower issue of the numbers of children involved. The director of the research programme, Professor Barry Carpenter, said in March that schools were struggling under “an avalanche of learning disabilities” (The Times, March 25 2011). If disabilities are really rising so rapidly, and the problem is real and not simply one of ascertainment, there must be some underlying reasons. What evidence does the research report provide?

On page 11 of the report the claims are made that between 2004 and 2009, the number of children with profound and multiple learning difficulties (PMLD) increased by 29.7 per cent; and that the prevalence of such serious disabilities is increasing among older children/young adults by 4-5 per cent a year.

The first claim is referenced to a publication by the Department of Children, Schools and Families (now Department for Education) in which I cannot find it. The second comes from research done for the Department of Health by Eric Emerson at the Institute for Health Research at Lancaster University. He calculates the rate of increase of children with PMLD from age-stratified data from a single year, 2008. Younger children are more likely to be classified as having PMLD than older ones, which he interprets as an increase in incidence of 4-5 per cent a year.

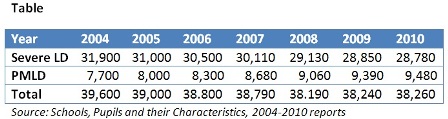

A more simple-minded approach is not to take a single year’s data, but to construct a time-series from the full run of data extracted from the annual Statistical Release on Schools, Pupils and their Characteristics for the relevant years.These show numbers of children classified as suffering PMLD as having risen from 7.700 in 2004 to 9.480 in 2010 – a rise of 23.1 per cent, or 3.3 per cent a year. (Statistics in this form do not exist before 2004.)

The comparable figure for the increase between 2004 and 2009 would be 21.9 per cent, not 29.7 per cent. However, there’s clearly a rise.

But this rise is accompanied by a fall in those suffering from severe learning difficulty, from 31,900 in 2004 to 28,780 in 2010. Those in the “severe” category have fallen almost exactly as fast as those in the “profound and multiple” category have risen. The table illustrates the point.

Oddly, the Schools Network report claims that between 2004 and 2009, the total number of children with severe learning disabilities increased by 5.1 per cent. Not according to DfE figures it didn’t (see table). It actually declined by 9.8 per cent. This claim is said to come from the same DCSF report, called Progression Guidance 2009-10, where I can’t find the 29.7 per cent figure either.

It’s tempting to suggest that what is going on here is a shift in diagnostic criteria that is increasing the numbers classified as PMLD while depleting those classified as severe. The other two categories, specific and moderate learning difficulty, show no clear evidence of any trend, up or down.

My suspicion, therefore, is that the apparent increase is an artefact. Such changes are common when a new diagnosis becomes fashionable – the rise in autism is a text-book example. But I can’t prove this.

If the increase in PMLD is real, it’s hardly an avalanche, but it still needs explanation. What changes could account for it?

The report suggests several. Medical advances are keeping children alive who would earlier have died, including those born very prematurely. That’s true, but I don’t think the numbers stack up (see earlier post).Foetal alcohol syndrome accounts for some cases, though how many is largely guesswork, as diagnoses by doctors miss many cases. And if numbers in this category were increasing, increases would be seen across the whole spectrum of disability, not just PMLD.

One issue the report doesn’t raise is the ethnic breakdown of PMLD, but it is provided by Dr Emerson. In 2008, 7.9 per cent of children in England with PMLD were of Pakistani origin, and 2.3 per cent Bangladeshi. This is between two and three times as high as these two populations’ share of live births.

The reason is the prevalence over many generations of cousin marriage in these communities. In Bradford, which has a large Pakistani community, genetic abnormalities in children are extremely high; the same is true of areas of Birmingham. Few in the white community have dared to criticise the practice of cousin marriage – two exceptions are Anne Cryer, the former Labour MP for Keighley, and geneticist Steve Jones – but it has plenty of critics among Muslims. It is perhaps surprising that the Schools Network report does not mention it as a possible cause of the rise in PMLD, since it appears more plausible than some it does mention.

Sumit Rahman (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 22/09/2011 - 12:56

I love these Nigel Hawkes articles ('the first number is claimed to be in publication X. But I looked at publication X and could not find it' etc etc). They really warn us that people are cavalier about using statistics to make their points - usually because they get away with it.

And an interesting final couple of paragraphs. It would have been better to have a reference for your claim that plenty of Muslims criticise "cousin marriage". (I'm a Muslim, and I am happy to criticise this practice, but who are the other Muslims who agree with me? There are clearly lots who don't, since this practice appears still to be prevalent.)